|

Debidutta Pattnaik Co-founder and Managing Director PRAGATI MARG FOUNDATION International Training Manager MICROLEND AUSTRALIA |

The positive role of Microfinance in Rural Development is applaudablewhen backed with a Social mission. However, mass-commercialization of the sector is a concern! Recent agitations of the Tamil farmers, protesting for the announcement of a drought relief package and loan waiver before the JantarMantar, and the recurring episodes of farmer’s suicide in India are evidences to what debt-distress is! It has both qualitative and quantitative implications. Propensity to debt and “indebtedness” is a growing risk in Microfinance. Post demonetization recoil in com mercial lending and the boom in financing activities backed by digitization may further dampen the situation, especially in Rural India. MFI sector showed resilience to change even in demonetization. It managed to close the year with an outstanding loan portfolio of ₹ 46,842 crores (approx.. $7.2 bn) with a fair CAGR of 16.15% over last four years. Today MFIs serve around 29 million clients with an average loan of ₹ 12,751 (approx. $196). Though the average loan is low and insignificant in figure; it has to be analysed from the perspectives of multiple borrowings, unproductive utilization, limited earning opportunities, slump in Agriculture, Industry and Manual Labor, and the ease of financing in the rising era of digitization.

Key Words: Debt-distress, Indebtedness, microcredit, microfinance, financial literacy

Agitation of the Tamil farmers staging protest in the national capital demanding announcement of a drought relief package and loan waiver of over 2000 Crores (approx. $308m), was back again! In 2017, the farmers made every attempt to express their anxieties in the state of their indebtedness. They walked naked, ate on the road, ate mice, drank urine, wore skulls symbolizing farmers who have committed suicide due to bad crop and unsettled loan etc. The returned episode was marked with some equally serious protests like its predecessor. Unfortunately such news are likely to be repeated, time and again, if the crux and core of the matter remains unresolved. While the plunders of big corporate scandals and fraudulence easily sneaks outdoor, the poor are utterly vulnerable left with limited choices of either terminating their ordeals `once-for-all’ or stage protests demanding media attention for influencing the policy makers! In such circumstances, MFIs cannot simply run with a commercial vision of profitability or anything beyond operational sustainability.

Indebtedness, as the state of being in debt, covers both personal and behavioural finance and is blended with positive and negative outcomes. On the positive side, people with easy access to debt have higher chances for financial wellness, provided the money is used for productive gain with risks adequately mitigated and (or) eliminated. The negative outcomes are desertion, distress and depression that fuels suicidal tendencies often culminating at self-killing! Such unpleasant incident potentially affect the present as well the future of a person. And often, the shock of indebtedness cascade down to a couple of generations!

Unfortunately some of our social extremes, living in remote hinterlands, get ensnared todebt in complete ignorance. In absence or negligible presence or reluctance to credit provision by the primary sector lenders, usury used to be a common factor leading to indebtedness in Rural India; but now the replacement seems to be the agenda of financial inclusion, especially from the creditors working with a commercial vision, and. Digital financial inclusion may further aggravate the situation though certainly it can potentially bring an end to the operational flaws of staff-frauds and misappropriation of collections which are the major impediments to the successful operation of MFIs, irrespective of their nature - commercial or social!

Over-indebtedness is rising globally. The growing risk in microfinance is over-indebtedness. (Kappel, Krauss, Lontzek; 2011).With such risk around, the industry is self-dampening its positive image. For a long time, it’s been widely celebrated as a source of financial services for people lacking access to primary source banking or with limited access to the major finance providers. Microfinance service providers enabled them to take loans in order to build or expand businesses and also make savings deposits.Unfortunately, the industry today is being criticised for the extent of its commercialization and the associated risk of mission drift (Allen 2007; Armendáriz and Szafarz 2009; Aubert, de Janvry and Sadoulet 2009; Cerven and Ghazanfar 1999; Copestake 2007; Drake and Rhyne 2002; Ferris 2008; Labie 2007; Mersland and Strøm 2010; Schicks 2007; Woller 2002).

Advantages i.e.,‘unbridled access to private capital without collaterals, professional service, and the unique potential for reaching out the 2.5 bn unbanked population of the world,’ were some of the unique features of microfinance operation. While the social mission of the microfinance industry gives specific importance to protecting the interest of customers, the 2008/2009 global banking crises has pointed out that irresponsible lending practices and unsustainable financial services impose threat not only to the customers but also for the Industry as a whole.

The industry is globally maturing. And it seems to be less prone to crisis than the formal financial sector. (Kappel, Krauss, Lontzek; 2011). But what is alarming is the degree of indebtedness that the vulnerable poor are exposed to with the growth of this industry worldwide. I think, at this point, it will be worth pointing out the progressive growth of this industry worldwide w.r.t. the founding vision, mission and strategic direction of this Industry.

Emergence and growth of Microfinance

The early literatures on microfinancing goes way back to the mid of 19 th century. Theorist Lysander Spooner advocated over the benefits of small credits to entrepreneurs and farmers as an effective means to battle poverty. Towards the end of World War II, with the Marshallianplan,this concept had a big impact.Timothy Guinnane, an economical historian at Yale, had made serious findings on the history of microfinance globally. His research on Friedrich Wilhelm Raiffesisen’s village bank movement in Germany revealed that in a span of 35 years (which started in 1864 and by the year 1901), the village bank had the potential to reach 2 million rural farmers. Timothy Guinnane meant that the mechanism of `banking to the poor’ had already proved the two vital tests on sustainability i.e. economies of scale and payback moral of the poor, in the mid of 19th century itself.

However, the present use of the expression “microfinancing” has its roots in the 1970s. This modern use began with the pioneering initiative of the Nobel Laureate, Dr. Mohammad Yunus who founded the organization, Grameen Bank which, for the first time, commercialized lending to the poor in Bangladesh. Another pioneer in this sector was Akhtar Hameed Khan. World was witnessing a new wave of microfinancing initiatives with many new advances into the sector during that period. Many pioneering enterprises began experimenting with loaning to the underserved people. The main reason behind crediting the emergence of microfinance to 1970s is that,during this period the programs revealed that even the poor are reliable and capable to repay their loans and that it was possible to render financial services to them through market based enterprises without subsidy. Though the concept of microfiance was not new to the world by 1970s, however in development circles, “the excitement over microfinance was exhilarating because it promised to achieve what previous models of development could not attain and marked the important turning point in human history. In fact it can be argued that, microfinance as a tool of poverty alleviation had taken on a religious fervour among its advocates since then.” (Lamia Karim, 2011).

Such excitement produced a new wave of evangelists for microcredit. In the 1990s, the consultative group to assist the poorest (CGAP) and donor agencies made microfinance a major donor plank for poverty alleviation and gender strategies. In 1997, when the first Microcredit summit was launched in Washington DC, research was presented in support of the notion that microfinance institutions are not only profitable and self-sustaining, but they are also capable of reaching and empowering large numbers of very poor women.

In 1997, the Microcredit Summit initiative reached only 7.6 million poor families; by the end of 2006, it had reached 100 million poor households. The goal of the summit was to reach 175 million poor households by 2015. Suchrising excitement resulted in declaring 2005 as the International Year of Microcredit by the United Nations. In 2006, when the Nobel Peace Committee conferred the Nobel Peace Prize on the Grameen Bank and its founder, Professor Yunus, it legitimized the microfinance model as key to poverty alleviation & women’s economic and social empowerment. These endorsements have resulted in an unprecedented escalation in funds promoting microfinance development. Even the industry practitioners had been propagating the concept that, Organizations with the best microfinancing practises had the potential to effect maximum poverty alleviation. However, Jonathan Morduch of the Princeton University (2000), in consultation with noted contemporary global economists i.e. Abhijit Banarjee, Gregory Chen, Monique Cohen, Peter Fidler, Mike Goldberg, Claudio Gonzalez-Vega, Albert Park, Marguerite Robinson, Richard Rosenberg, Jay Rosengard, J.D. Von Pischke, Jacob Yaron and other participants at the lively seminars at Ohio State and the World Bank, had made an opinion that neither logic and nor empirical evidence justified the myth that microfinance institutions that follow the principles of good banking will also be those that alleviate the most vulnerable poor out of poverty.And he was so right in making such contrary opinion especially at a time when the world was celebrating the gigantic success of this idea. In alignment to the views of Murdoch I strongly feel and sense that, in the present context, the industry is facing severe criticism based on what it promised and what is being actually achieved in the ground. Especially lost in the battle of mass commercialization!

Rising episode of Indebtedness

The growing risk of over-indebtedness has put the long celebrated achievements of microfinance at risk. (Schicks, 2010). Freedom from poverty is not free, and the resulting strain on the indebted clients due to the recovery practices of Microfinance Institutions (MFIs) has been a matter of debate and concern. (Ramachandran, 2002; Young, 2010; Taylor, 2011; Kar, 2013; Mader, 2013). The Industry is largely commercialized.

Recent research by independent scholars in Bangladesh documents that microfinance policies undertaken by Grameen Bank and the leading microfinance institutions (NGOs) do not benefit the poor.(Lamia Karim, 2011) Unfortunately, such researches are relatively unknown outside Bangladesh because the robust critical discourse regarding microfinance is available in the vernacular literature in Bangladesh which is not accessible to western readers. In fact, the study of Dr. Lamia Karim was of paramount importance in this regard. It was a kind of eye-opener to the western world based on the fact that, Dr. Karim being a scholar from Bangladesh origin had made some significant exposures about the actual nature and practice of the Industry, right in the place where it got the international acclamation. His research has conveyed the right message on the actual impact of microfinance in the lives of poor women in the heart land of Microfinance.

In his research, Dr. Karim discovered that the real users of microfinance loans were seldom the women themselves.Their position remained widely vulnerable to the other male members of the family and hence the correlation of microfinance and women empowerment was questionable. He also argued that the vision of a microfinance institution was seldom social, an MFI only lends loan after ascertaining the ability of the client to repay. In other words, the financing decision of an MFI is not based on the level of poverty of the client but rather on the client’s capacity to repay. Thus a sharp shift of focus of the industry, from social actions to commercialization was sighted here.

In another extensive study by an IIM (A) scholar, it was highlighted that the credit policies of the Grameen Bank do not constitute a sufficient explanation for the bank’s success, and that its acclaimed policy of replacing individual collateral with group guarantee is in fact not practised. (Jain, 1999). In one of the latest ethnographic study of three villages in Bangladesh, it was revealed that microfinance led to increasing level of indebtedness among already impoverished communities and exacerbated economic, social and environmental vulnerabilities. (Banerjee, Jackson; 2016).In such context, the widespread popularity and growth of Indian MFI, call for some serious inspection. On a global scale, the Industry is achieving its fastest growth in South Asia and India is in fact leading the race in the region.

Microfinance in India had suffered some major setback in the recent past. The endemic death episode, over-indebtedness, and coercive recovery practices of the Industry had together contributed to the suicidal epidemic of Andhra Pradesh in 2010.However, the current trend suggests that the industry has brushed off all stains and is on its topmost gear to fast recovery, growth and progress; despite the fact that the visible motivation of this Industry is profit maximization and not poverty alleviation.And the situation may further worsen with the backing of digitization of rural banking.

The objectives of my study are to:

1. Explore the menace of indebtedness/debt-distress in India

2. Identify the current position and operational motive of Indian MFIs.

I would like to nomenclate it as an exploratory study. Data comprised of both primary and secondary sources i.e. Books, Journals, Research Papers, Industrial Reports and Publications, Internal Data of Pragati Marg Foundation, News Papers etc. were referred during the course of the research. Different websites were also studied to feed in the required data. A few online polls were conducted to supplement this research. Method of cross referencing was also adopted during the course.

Major Findings

Growing level of indebtedness in India

Indebtedness can be defined as the state of being in debt. It’s on a constant rise in the nation. Though it’s a vast topic to deal with, during the course of the research, I came across some key data which reveals the grave situation of indebtedness in India.

The National Sample Survey Organization (NSSO) in 2012revealed that 22% of the urban households were indebted and the average debt per family was ₹ 84, 625 (approx. $1300). It’s about seven times higher than the corresponding figure in 2002. In rural areas, the level of indebtedness was even higher at 31% compared to 27% in 2002. The average debt had increased four times from ₹ 7539 (approx. $116) in 2002 to Rs.32,522 (approx.. $ 500) by 2012. A better picture of the scale of indebtedness was seen when the total debt was distributed only over the indebted households. The average debt in rural areas increased to ₹ 1,03,457 (approx. $1600) and the urban debt increased to ₹ 3,78,238 (approx. $5800). This survey studied the assets and liabilities across India through two visits on more than hundred thousand households.

The current stake of MFIs towards indebtedness is presented with the help of aChart:

(Refer Figure 1)

Though the average loan size appears very low and insignificant; the net effect of limited income sources coupled with slump in agriculture, Industry and manual labour and the risk of multiple borrowings per person or household especially for consumption, may aggravate the issue of indebtedness much further than the figure cited above. Unfortunately, empirical data is limited to uncover the issue for the whole nation. The focus of the industry seems zooming back to villages and this could lead to serious problems of indebtedness especially in the rural region.

(Refer Figure 2)

Though the average loan per borrower is below the national average for East, Northeast and Central; but the figures of North, South and West could be a concern. Increasing level of indebtedness means increasing concerns.

Factors affecting Indebtedness

An online poll made the following claims as factors leading to indebtedness.

(Refer Figure 3)

‘Indebtedness is primarily due to financial indiscipline.’ Nearly 31% of the respondents in an online poll made such opinion. Indebtedness was associated to cognitive behaviours i.e. habit and lack of control by 25%. Around 35% said that, it emerges out of compulsive vulnerable situation of a client and financial illiteracyof a poor consumer. As high as 73% of the respondents associated the intensity of indebtedness to be measured w.r.t. the monthly income (gross and disposable) of the client. 90% agreed that indebtedness leads to depression. 85% of the respondents agreed that indebtedness triggers suicidal tendencies and 98% of the population believed that people in (over) indebtedness need help. Around 68% said, people in indebtedness need financial, especially debt literacy and about 21% opined in favour of the provision of low cost loans to clear off high cost debts of people in debt!

Though the size of the survey data (about 48 respondents) was very low to make any conclusive opinion, I think the sample was significant enough to unveil the causes and some of the alarming effects associated to indebtedness. Today, debt provision is considered as the primary agenda of financial inclusion. At this juncture, the role of MFIs (Microfinance Institutions) as a debt provider and the resulting consequences, may be a cause of concern in the long run!

The widespread prevalence of women illiteracy (functional literacy) is a major impediment to financial literacy. As practitioners and activists for socio-economic justice of the poor, we have encountered serious issues in the level of comprehensibility of the illiterate women in rural region. At this juncture, unbridled provision of micro-credit in hands of illiterate women will end up producing worse results.

The alarming consequence of debt-distress – Farmer’s Suicide in India

I don’t want to link microfinance as the exclusive reason to the menace of farmers’ suicide. However, the impact of microfinance in causing debt-distress cannot be negated as seen during the crisis of SKS in Andhra Pradesh in 2010.

Data clearly suggests a rising level of indebtedness in the nation. And therefore, the incidence of farmer suicide being connected to indebtedness shouldn’t be a surprise at all. Famers’ suicide over a period of 16 years (derived from various sources available on internet) is depicted with the help of a bar chart.

(Refer Figure 4)

It should be noted here that many of the suicidal deaths doesn’t get reported in India. So the figure appearing in the chart is quite alarming. In the NCRB’s report 2014, the Bureau revealed that, bankruptcy lead to 20.6% of the suicides for the year and family problems were cause for 20.1%, crop failure led to 16.8% of the cases which may indirectly be associated to indebtedness, illness was 13.2%, drug abuse or alcohol addiction was 4.9%.

Former reports had revealed that 72.4% of the total farmers who committed suicide were either marginal or small farmers with minimum land holding or assets. Thus indebtedness was an alarming concern at least for those who decided to quit their life succumbing to either an internal or external cause! Unfortunately, the menace of indebtedness is on constant rise leading to deplorable outcomes while the picture of financial literacy is gruesome in India. Over these conditions, incidents like the Tamil farmers’ protest, may appear funny to many, but is a cause of national concern. Something has to be done and at the earliest. Though personally, I don’t feel, loan waivers would do any good in the long run!

Position of Indian MFI

Microfinance exists in two models in India, the MFI (Microfinance Institution) model and the SHG (Self Help Group) model. The later primarily gets linked to the formal banks who take the savings of the clients and also offer credit to the customers. MFIs currently operates in 29 states and 4 union territories covering 563 districts (out of the 707 districts) in India. Thus on a national administrative division level, the penetration percentage of the industry is about 80%.

The size of the industry is growing every year with a CAGR of over 16.15% in the past four years. There was a dip of 26.64% in the overall portfolio outstanding for the year 2017. However, the industry seems to bounce back heavily. Before the end FY 2017, the industry has grown up to Rs.468.42 bn (approx. $ 7.2 bn) despite the deterrence of demonetization.

(Refer Figure 5)

Data is suggestive of the fact that Indian Microfinance market has the potential to grow both horizontally as well as vertically. Horizontal spread of the sector was marked by the increasing number of clientele and vertical growth was through the rising level of average loan per client. And the later strategy may seriously affect the overall position of indebtedness in the rural region.

MFIs moving back to Rural India

(Refer Figure 6)

There was a steady decline of MFIs in rural areas which was being compensated by their increasing presence in the urban set-ups. MFIs in India were consolidating their rural operation and were proportionately growing in urban areas. Growing risk of loan losses among the poor and vulnerable rural population with high probability of livelihood shocks and the resulting NPAs or loan defaults, operational hazards etc. weresome of the probable factors attributed to this drifting vision. However, the latest trend is suggestive of the fact that MFIs are beginning to reposition themselves in the heart of India. And this could be a matter of concern in the near future. Villagers with limited opportunities and earning potential may soon face the heat of disciplined collection process via joint liability and group guarantee where the good is always forced to suffer for the evil i.e. the regular paying members are compelled to recompense for the defaulting members. And the noble vision of digitizing India may add more opportunities for the rising level of indebtedness among the rural population.

Disparity in MFIs concentration

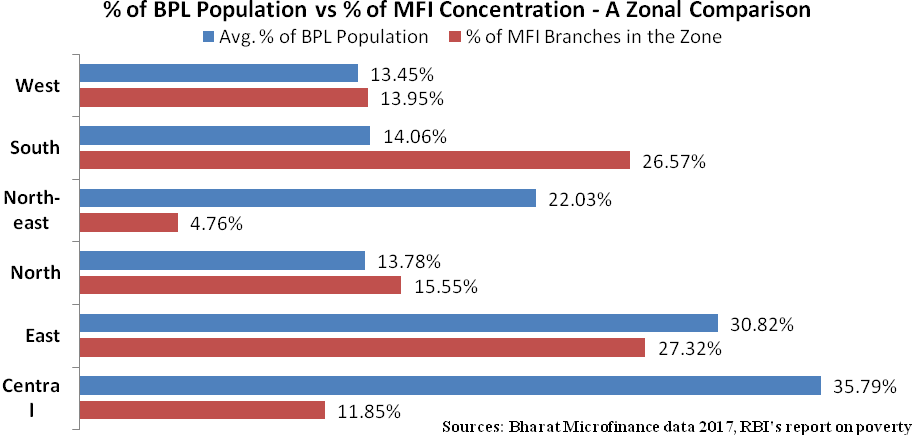

(Refer Figure 7)

The chart compares the percentage of MFI branches (out of the total branches) in India vis-a-vis the percentage of BPL population in the zone. The data is matched zone-wisebased on the reports published by RBI. As per the Zonal Maps of India, East zone comprises of the Indian states of West Bengal, Odisha, Jharkhand and Bihar. South Zone comprises of Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh and Telengana, Kerala, Puducherry, Andaman and Nicobar Island. The Northeast zone comprises of Assam, Tripura, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Sikkim, Arunachal Pradesh, Nagaland. West Zone comprises of Maharasthra, Gujarat, Rajasthan, Goa. The north Zone comprises of Uttarpradesh, Delhi, Uttarakhand, Haryana, Punjab, Chandigarh, Himachal Pradesh, Jammu and Kashmir. And the Central Zone comprises of the states of Madhya Pradesh and Chattisgarh.

The chart clearly portrays the zonal focus of MFIs in India. Though there is a match to the concentration of MFIs with respect to the below poverty line population in the West and North Zone; there is a significant mismatch in the figures in Northeast and Central Zone with a fairly good reach in the East Zone.

Another interesting observation noted here is, despite the lower percentage of BPL population in South, MFIs concentration is at its peak. Nearly 30% of all MFI branches are placed in the south zone. What would be interesting here is to know, who are the actual clients of MFIs in this region? Are the MFIs actually serving the poor? Even if for the sake of argument, if it’s assumed that, all the beneficiaries of MFI in south India are actually poor, then what about the SC/ST Population of the region?

Reach of MFIs to the SC/ST Populations is low.

The national average of SC/ST population in Rural India is around 30%. However, the factual claim is clearly an indication of the fact that many of the all-time poor are yet to taste the first fruit of financial inclusion.

(Refer Figure 8)

As a practitioner of social financial inclusion, we began our journey in some of the hardest areas of Aravali in the year 2010. About cent percent of our beneficiaries had been Tribal of the region who serve as an epitome of unspeakable misery.

Some of the major impediments to the holistic development of the region are: poverty, usury (monthly interest ranging from 5-10% with collaterals), illiteracy, and negligible infrastructure, etc. There are many reasons for the rugged conditions of the people living in the Aravali Ranges of Southern Rajasthan, particularly the Girva Region of Udaipur District, e.g. illiteracy, large families, underutilized barren land, lack of irrigation facilities leading to fewer Rabi Crop cultivations, with one of the leading factors being the tyranny of nature expressed in form of extreme geographical and geological conditions for the locale.

However, we have witnessedsome impressive growth in their Agriculture and agro-based allied activities for economic sustainability. Despite the challenges of unqualified staffs, difficult terrain, dryness and ruggedness of land, we could achieve some positive result in this short discourse of time. However, phenomenal results could be seen if we are supported by more like-minded agencies operating in the region.

At this juncture, it’s both and encouragement and concern in knowing that, MFIs are shifting back focus to rural region. Certainly they are needed in places where the need is high. And MFIs working with a social vision to supplement such growing need is matter of appreciation. However, the concern isthe underlying motive behind such operations. Because more than financing and financial facilitation, what’s required in rural India is commendable self-sustaining education to elevate the level of skill, knowledge and attitude of the vulnerable poor.

(Refer Figure 9)

The mounting bar of 2017 vs. 2016 clearly depict the position of MFIs in Rural areas going back to the level of 2014. MFIs in India were consolidating their rural operation and proportionately growing in urban areas and this trend is altered by 2017. I hope this trend is to last long, ending up doing good in the long run.

MFI sector in India is showing resilience to change. Even the unprecedented factor of demonetization couldn’t impact the industry much. Over the last decade, the microfinance industry has certainly achieved phenomenal growth and public praise for its proclamation to end world poverty. But the growth of the industry compared to the risk of indebtedness and vulnerability of the poor, especially in the rural region, is a matter of concern.

The dreadful story of farmer’s suicide resulting from indebtedness could be avoided if the facilitators of credit could shift their focus from being just a commercial entity to becoming agents and proponents of socio-economic transformation. Thus what’s needed more in ground is social agencies propelled with a missionary vision! Commercial entities with for-profit mission isdeterrence to the progress of poor, especially in the rural region. And as for Microfinance Operations, it’s a well-known fact that this sector received all public praises and accolades because of its power to alleviate poverty and bring social justice to the suffering and poor. However, in due course of time, it’s shifting itself from being a social entity to more of a commercial one.

At the end, I would like to state that, there is lot to be done from the scholarly fraternity in reading and analysing empirical evidences on any claims made by Institutions. I hope this paper will ignite some interest and bring the attention of its readers towards the issues elaborated throughout the paper.

Biswas, Southik (2010, December 16). India’s micro-finance suicide epidemic. BBC News. Retrieved from http://www.bbc.com/news/world-south-asia-11997571 (Accessed on September 5, 2016)

Districts. Government of India Web Directory. Retrieved from http://goidirectory.gov.in/district.php (Accessed on September 10, 2016)

Farmers Suicide in India. National Crime Records Bureau, Government of India. Retrieved from http://ncrb.gov.in/StatPublications/ADSI/ADSI2014/chapter-2A%20farmer%20suicides.pdf (Accessed on September 10, 2016)

Jain, Pankaj. S. (1996). Managing Credit for the rural poor: Lessons from the Grameen Bank. World Development, The Multi-disciplinary International Journal Devoted to the Study and Promotion of World Development, Vol. 24, Issue 1, Pages 79-89.

Jackson, Laurel.,& Banerjee, Subharata. Bobby (2016). Microfinance and the business of Poverty reduction: Critical Perspectives from rural Bangladesh. Human Relations. Sage Journals. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/303029935_Microfinance_and_the_business_of_poverty_reduction_Critical_perspectives_from_rural_Bangladesh (Accessed on September 5, 2016)

Kalam, A.P.J. Abdul & Singh, Srijanpal (2011). Target 3 Billion: Innovative Solutions Towards Sustainable Development. New Delhi, India: Penguin India

Kar, Sohini (2013). Recovering Debts: Microfinance loan officers and the work of “proxy-creditors” in India. American Ethnologist, The Journal of American Ethnological Society, Vol. 40, Issue 3, Pages 480-493.

Karim, Lamia (2011). Microfinance and Its Discontents: Women in Debt in Bangladesh. Minneapolis, US: University of Minnesota Press.

Mader, Philip (2013). Rise and Fall of Microfinance in India: The Andhra Pradesh Crisis in Perspective. Journal of Strategic Change, Vol. 22, Issue 1-2, Pages 47-66.

Morduch, Jonathan (2000). The Microfinance Schism. World Development, Vol. 28, No. 4, pp 617-629. Great Britain: Elsevier Science Ltd. Retrieved from http://www.nyu.edu/projects/morduch/documents/microfinance/Microfinance_Schism.pdf (accessed on September 16, 2016)

Pattnaik, Debidutta (2016). Indebtedness study. Retrieved from https://www.surveymonkey.com/results/SM-BP7FBY2X/ (accessed on October 1, 2016)

Pattnaik, Debidutta (2017). Indebtedness and Financial Inclusion: The Alarming Outcome of Commercial Microfinance in India. Pratibimba – The Journal of IMIS, Vol. 17, Issue 1. Pp 23-30.

Pattnayak, Naresh Chandra (2016, February 16). Widow pawns sons to pay for husband’s funeral. Times of India News. Retrieved from http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/bhubaneswar/Widow-pawns-sons-to-pay-for-husbands-funeral/articleshow/51032509.cms (Accessed on September 10, 2016)

Poverty in India. Wikipedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Poverty_in_India&oldid=736980343 (Accessed on September 14, 2016)

Bhatia, Asha.,Shivkumar, S.N.V., and Agarwal, Ankit (2016). A Contemporary study of Microfinance: A study for India’s Underprivileged. Journal of Economics and Finance, 2016,23–31. Retrieved from http://www.iosrjournals.org/iosr-jef/papers/SIFICO/Version-2/3.23-31.pdf (accessed on September 14, 2016)

ResponsAbility Investment AG. (2015). Microfinance Outlook 2016. Retrieved from http://www.responsability.com/funding/data/docs/en/17813/Microfinance-Outlook-2016-EN.pdf (accessed on September 13, 2016)

Sa-Dhan (2014). The Bharat Microfinance Report 2014. Retrieved from http://www.sa-dhan.net/Resources/Finale%20Report.pdf (Accessed on September 7, 2016)

Sa-Dhan (2015). The Bharat Microfinance Report 2015. Retrieved from http://indiamicrofinance.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Bharat-Microfinance-Report-20151.pdf (Accessed on September 7, 2016)

Sa-Dhan (2016). The Bharat Microfinance Report 2016. Retrieved from http://indiamicrofinance.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/The-Bharat-Microfinance-Report-2016.pdf (Accessed on September 9, 2016)

Sa-Dhan (2017). The Bharat Microfinance Report 2017. Retrieved from http://indiamicrofinance.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/The-Bharat-Microfinace-Report-2017-Final.pdf (Accessed on March 3, 2018)

Shicks, Jessica (2010). Microfinance over-indebtedness: Understanding its drivers and challenging the common myths. Solvay Brussels School of Economics and Management, Centre Emile Bernhein, Brussels, Belgium: Unpublished Manuscript. Retrieved from http://www.csae.ox.ac.uk/conferences/2011-edia/papers/296-Shicks.pdf (accessed on September 16, 2016)

State-wise Percentage of Population Below Poverty Line by Social Groups, 2004-05. Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, Government of India. Retrieved from http://socialjustice.nic.in/UserView/index?mid=76672 (Accessed on September 10, 2016)

Taylor, Marcus (2011). Freedom from Poverty is not Free : Rural Development and the Microfinance Crisis in Andhra Pradesh, India. Journal of Agrarian Change, Vol. 11, Issue 4, Pages 484-504.

Taylor, Marcus (2012). The Antimonies of Financial Inclusion: Debt, Distress and the Workings of Indian Microfinance. Journal of Agrarian Change, Vol. 12, Issue 4, Pages 601-610.

Varma, Subodh (2014, December 22). 22% of households in cities, 31% in villages are in debt. The Times of India News. Retrieved from http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/22-of-households-in-cities-31-in-villages-are-in-debt/articleshow/45597822.cms (Accessed on September 10, 2016)

Young, Stephen (2010). The Moral Hazards of Microfinance: Restructuring Rural Credit in India. Antipode A Radical Journal of Geography, Vol. 42, Issue 1, Pages 201-223.

Zonal Maps of India. India Zonal Map. Retrieved from http://www.mapsofindia.com/zonal/ (Accessed on September 14, 2016)

Figures

Figure 1

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 6

Figure 7

Figure 7

Figure 8

Figure 8

Figure 9

Figure 9