|

Dr. Sakshi Sharma Assistant Professor DFaculty of Management Sciences & Liberal Arts Shoolini University Solan, HP |

The present study was conducted among 76 research scholars of universities of Himachal Pradesh. The study sought to determine the effect of impostor phenomenon on career satisfaction and perceived career success of scholars with career optimism as a mediator variable. The participants completed Clance Impostor Scale and two scales measuring career satisfaction and perceived career success. The results of the study supported the hypotheses (a) Impostor Phenomenon was negatively related to career satisfaction and perceived career success of research scholars; (b) career optimism mediated relationship between impostor phenomenon and career satisfaction perceived career success of research scholars.

Keywords: Impostor phenomenon, career satisfaction, perceived career success, career optimism Classification Code: Y80

The term ‘Impostor Phenomenon’ was coined by Pauline Clance and Suzanne Imes in 1978. IP refers to an “internal experience of intellectual phoniness” (Mattews & Clance, 1985) in individuals who are highly successful but unable to internalise their success (Sakulku & Alexander, 2011). A high level of impostor phenomenon limits the acceptance of success as an outcome of one’s own ability and influences feelings of self-doubt and anxiety (Sakulku & Alexander, 2011). According to Langford and Clance (1993) IP is “believing that one’s accomplishments came about not through genuine ability, but as a result of having been lucky, having worked harder than others, and having manipulated other people’s impressions.” One key aspect of impostor syndrome is the attribution of one’s success to factors beyond one’s control, such as luck, while attributing the success of others to skill or knowledge (Ivie & Ephraim, 2011). Impostors seldom attribute their success to innate skills and abilities. Research has shown that a large proportion of people have felt like impostors at some time of their life. Although Impostor Phenomenon was initially applied to only high-achieving women, however, subsequent studies have shown that men also experience Impostor Phenomenon to a similar level. IP plays an important role in the outcomes of an employee. For instance, IP can affect future achievement on the part of an employee (Clance & O’Toole, 1988). According to Clance and O’Toole, feelings of inadequacy, such as those accompanying the imposter phenomenon, can affect individual’s ability to function at highest level.

The feelings associated with Impostor Phenomenon are paradoxical. Individuals who experience feelings of IP present themselves as confident and capable people. However, they also tend to attribute much of their career success factors like luck, “being in the right place at the right time”, or quota-filling, rather than to their own capabilities and skill. IP individuals tend to be perfectionists, have a fear of letting people down or disappointing others, and thus have a fear of failing (Gannon, 2016). In addition, they also have fear of success. Individuals experiencing IP feel that somehow they do not deserve the success they have achieved. Therefore, they become anxious about being discovered that they do not really belong in that role (Gannon, 2016).

In the career domain, researchers have found Impostor feelings linked to less career planning (Neureiter & Traut-Mattausch, 2016), and also a barrier to move up higher in the occupational levels and leadership positions (Neureiter & Traut-Mattausch, 2016). Researchers have also found IP negatively related to job satisfaction (Vergauwe et al., 2015). However, career satisfaction extends beyond job satisfaction as it concerns not only person’s present job but also his entire career (Neureiter & Traut-Mattausch, 2016). The term ‘career’ is the lifelong sequence of role-related experience of individuals (Hall, 2002). Career satisfaction is the satisfaction that individual derives from the intrinsic and extrinsic aspects of their careers, including pay, advancement, and developmental opportunities (Greenhaus, Parasuraman, & Wormley, 1990). Career success is the accumulation of achievements (real or subjective) arising from one’s work experiences (Judge, Cable, Boudreau & Bretz, 1995). It is suggested that the feelings of impostorism may cause feelings of dissatisfaction in relation to one’s career and also may have an impact on one’s perceived career success. Thus, the purpose of the present study is to examine the influence of impostor phenomenon on one’s career satisfaction and perceived career success.

Career optimism is a predisposition to expect the most promising outcome or to lay emphasis on the most affirmative features of one’s future career development, and comfort in performing career planning tasks (Rottinghaus, Day & Borgen, 2005). Optimistic individuals are assumed to “expect the best possible outcome or to emphasize the most positive aspects of [their] future career development and [be comfortable] performing career planning tasks” (Rottinghaus, Day & Borgen, 2005). Spurk and Volmer (2013, as cited in Neureiter & Traut-Mattausch, 2016) in their research found that employees with high career optimism had high career and job satisfaction and higher other-referent subjective career success. Therefore, in the present study it is also expected that optimism would mediate the relationship between Impostor Phenomenon and career satisfaction and perceived career success such that less career optimism would lead to less career satisfaction and low perceived career success.

Numerous studies have demonstrated the prevalence if Impostor Phenomenon in academia. Studies have documented the prevalence of IP in undergraduate (Ferrari & Thompson, 2006) and graduate students (Mattie, Gietzen, Davis & Prata, 2007). Researchers have also demonstrated presence of IP even at doctoral programs (Long, Jenkins, & Bracken, 2000 ) In an interview published in McGill Reporter, Diane Zorn stated that “scholarly isolation, aggressive competitiveness, disciplinary nationalism, a lack of mentoring and valuation of product over process are rooted in university culture” and therefore “students and faculty are particularly susceptible to IP feelings” (McDevitt, 2006). Kets de Vries (as cited in Clark, Vardeman & Barba, 2014) also theorized that there is a higher incidence of the impostor phenomenon in academia because the appearance of intelligence is the key to personal success. The present study is therefore an attempt to understand the impostor phenomenon of research scholars and its impact on their career satisfaction and perceived careers success.

Hypothesis

H1: Impostor Phenomenon will be negatively related to career satisfaction of research scholars.

H2: Impostor Phenomenon will be negatively related to perceived career success of research scholars.

H3: Career optimism would mediate the relationship between Impostor Phenomenon and career satisfaction of research scholars.

H4: Career optimism would mediate the relationship between Impostor Phenomenon and perceived career success of research scholars.

Participants and Procedure

The study is based on primary data collected through a survey conducted on the sample consisting of 76 Ph.D. research scholars of various universities of Himachal Pradesh. In order to get the required information a well designed questionnaire was prepared and administered among respondents. Data was collected from universities located in Shimla and Solan area of Himachal Pradesh. Questionnaires were distributed to 110 researchers, of which 76 questionnaires were returned, yielding a response rate of 69% respectively. The respondents were selected using convenience and judgement sampling techniques. The data thus collected have been analyzed with the help of SPSS 21.

Measures

Impostor Phenomenon: Impostor Phenomenon was measured using Clance Impostor Phenomenon Scale. The scale comprises 20 items that assess various aspects of IP, using a Likert format (Clance, 1985). Participant rated their agreement or disagreement using a five point scale (1=not at all true to 5= very true). The scale had a reliability of α=.92 in the present study.

Career Satisfaction Scale: Career satisfaction was measured using a scale developed by Greenhaus, Parasuraman, and Wormley (1990). The scale comprises five items rated on a five point scale (1= strongly disagree to 5= strongly agree). One sample item is “I am satisfied with the progress I have made toward meeting my overall career goals.” The scale had a reliability of α=.84 in the present study.

Perceived Career Success: Perceived career success was measured using a scale developed by Turban and Dougherty (1994). The scale comprises four items rated on a five point scale (1= very dissatisfied to 5= very satisfied). One sample item is “I am satisfied with the success I have achieved in my career.” The scale had a reliability of α=.80 in the present study.

Career Optimism: Career Optimism was measured using a four item subscale of Career Future Inventory-Revised by Rottinghaus et al. (2012). The items were rated on a five point scale (1= strongly disagree to 5= strongly agree). The negatively worded items were rephrased for better understanding of the respondents. One reworded sample item is “I am confident that my career will turn out well in the future”. The scale had a reliability of α=.92 in the present study.

Correlation Coefficients

In order to find out the relationship between impostor phenomenon and career satisfaction and perceived career success of research scholars, Pearson correlation coefficient was employed and the results are shown in Table 1. Impostor phenomenon was found to be significantly and negatively correlated with career satisfaction (r=-.75**, p<.01) and perceived career success (r=-.61**), thereby supporting Hypotheses 1 and 2.

Table 1 : Correlation coefficient between impostor phenomenon, career satisfaction and perceived career success

|

|

Career Satisfaction

|

Perceived Career Success |

|

Impostor Phenomenon |

-.75**

|

-.61** |

Note: **Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

Mediating Effects

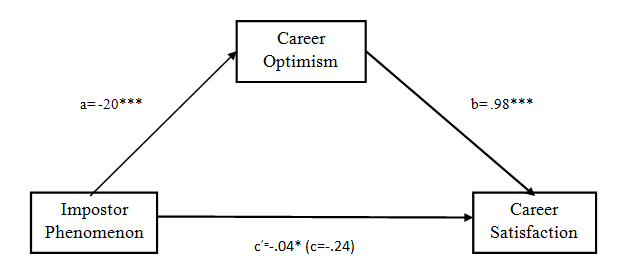

To investigate the proposed hypotheses bootstrapping approach proposed by Preacher and Hayes (2004) with recommended 5000 samples was used. Indirect Pathway c’ (the effect of X on Y, when MV is controlled) was calculated using PROCESS macro produced and offered by Hayes (2013). See Fig. 1 and Fig.2 for an illustration of the proposed mediation models. The relation between the variables indicates that it will be beneficial to conduct mediation analysis further.

Impostor Phenomenon and Career satisfaction

First, it was found that Impostor Phenomenon was negatively associated with career optimism of research scholars (B= -.20, t (74) = -9.26, p =.000). It was also found that Impostor Phenomenon also related significantly and negatively to career satisfaction (B= -.04, t (74) = -2.53, p=.013). Lastly results indicated that mediator, career optimism, was positively and significantly associated with career satisfaction (B=.98, t (74) = 16.34, p = .000). Because, both the a-path and b-path were significant, mediation analysis was tested using bootstrapping method with bias-corrected confidence estimates. In the present study, the 95% confidence interval of the indirect effect was obtained with 5000 bootstrap re-samples. Results of the mediation analysis confirmed the mediating role of career optimism in the relation between Impostor Phenomenon and career satisfaction (B= -.20, CI= -.2582 to -.1480). The result also indicated that the previously significant relationship between predictor (Impostor Phenomenon) and the outcome (career satisfaction) remained significant (B= -.04, CI= -.0758 to -.0091). Therefore, Sobel test was conducted which suggested partial mediation in the model (z=-8.04, p =.000). Figure 1 displays the results. Hence, hypothesis H3 is accepted.

Figure 1 : Indirect Effect of Impostor Phenomenon on Career Satisfaction through Career Optimism

Note : * p <.05, ** p <.01, *** p <.001

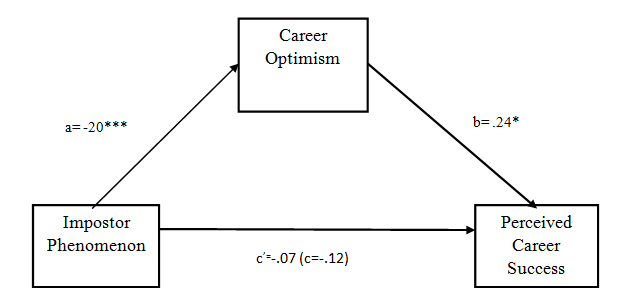

Impostor Phenomenon and Perceived Career Success

Multiple regression analysis was also conducted to assess each component of the mediation model presented in Figure 2. First, it was found that Impostor Phenomenon was negatively associated with career optimism of research scholars (B= -.20, t (74) = -9.26, p =.000). It was also found that Impostor Phenomenon also related negatively to perceived career success (B= -.07, t (74) = -2.90, p =.004). Lastly results indicated that mediator, career optimism, was positively associated with perceived career success (B=.24, t (74) = 2.51, p = .014). Because, both the a-path and b-path were significant, mediation analysis was tested using bootstrapping method with bias-corrected confidence estimates. In the present study, the 95% confidence interval of the indirect effect was obtained with 5000 bootstrap re-samples. Results of the mediation analysis confirmed the mediating role of career optimism in the relation between Impostor Phenomenon and perceived career success (B= -.05, CI= -.1097 to -.0071). The result also indicated that the previously significant relationship between predictor (Impostor Phenomenon) and the outcome (career satisfaction) remained significant (B= -.07, CI= -.1338 to -.0250). Therefore, Sobel test was conducted which suggested partial mediation in the model (z=-2.41, p =.015). Hence, hypothesis H4 is accepted.

Figure 2 : Indirect Effect of Impostor Phenomenon on Perceived Career Success through Career Optimism

Note : * p <.05, ** p <.01, *** p <.001

The study aimed to examine the relationship between impostor phenomenon, career satisfaction and perceived career success. As predicted, impostor phenomenon was found to be significant and negatively related to career satisfaction as well as perceived career success. Neureiter & Traut-Mattausch, (2016) in their study also reported negative correlation between impostor phenomenon and career satisfaction and other- referent career success. Furthermore, the present study also investigated the indirect effects using mediation analysis. The role of career optimism, mediator variable, was found to be significant in the relation between impostor phenomenon and career satisfaction. In addition, career optimism was also a significant mediator in the relation between impostor phenomenon and perceived career success. The results are supported by the findings of the study by Neureiter & Traut-Mattausch, (2016) who reported optimism as the most prominent mediator in the negative relation between the impostor phenomenon and subjective career success. Studies in the past have shown that career optimism not only makes individual happier, but enhances their prospects of promotion and has beneficial impact on work productivity (Neureiter & Traut-Mattausch, 2016). Researchers have demonstrated the positive correlations of IP with one’s academic success (Thompson Davis & Davidson, 1998), achievement orientation (King & Cooley, 1995) and also its negative correlations with self-esteem (Kolligan & Sternberg, 1991) academic self-efficacy (Thompson Davis & Davidson, 1998). IP is an important factor in the performance of an individual as it might decrease a person’s motivation to pursue goals. Therefore, it becomes important to address the issues related to impostor feeling among research scholars. In an effort to keep students safe and to retain them, a number of universities and colleges have now developed programs on impostor phenomenon. IP also has become an essential part of orientation events for students (Parkman, 2016). The present study adds to the current literature by demonstrating the effect of impostor phenomenon on career satisfaction and career success. However, although the results of the present study are as expected, the mediation effect of career optimism on career satisfaction and career success occurred only partially. Hence, it is conceivable that other mediators aside from those examined herein contribute to the effects on the dependent variables. Therefore, in future more empirical research can be conducted in this area by integrating additional variables in multiple mediation analysis.

Clance, P.R. (1985). The impostor phenomenon: Overcoming the fear that haunts your success. Atlanta, GA: Peachtree.

Clance P, & Imes, S. (1978). The impostor phenomenon in high-achieving women: Dynamics and therapeutic intervention. Psychotherapy : Theory, Research, and Practice, 15, 241-247.

Clance, P. & O’Toole, M. A. (1988).The impostor phenomenon: An internal barrier to empowerment and achievement. Women and Therapy , 6, 51-64.

Clark, M., Kimberly, V., & Shelley, B. (2014). Perceived inadequacy: A study of the impostor phenomenon among college and research librarians. College & Research Libraries, 75(3), 255-271.

Ferrari, J. R., & Thompson, T. (2006). Impostor fears: links with self-presentational concerns and self-handicapping behaviours. Personality and Individual Differences, 40(2), 341-352.

Gannon, M. (2016). You’ve got this: Overcoming imposter syndrome. Accessed from https://vanderbiltbiomedg.com/2016/11/16/youve-got-this-overcoming-imposter-syndrome/ [May 3, 2017]

Greenhaus, J. H., Parasuraman, A., & Wormley, W. M. (1990). Effects of race on organizational experiences, job performance evaluations, and career outcomes. Academy of Management Journal, 33(1), 64-86.

Hall, D. T., & Chandler, D. E. (2005). Psychological success: When the career is a calling. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26, 155–176

Ivie, R. & Ephraim, A. (2011). Women and the impostor syndrome in astronomy. STATUS: A Report on Women in Astronomy. Accessed from https://lavinia.as.arizona.edu/~timestep/aip_impostersyndrom_2015.pdf [May 5, 2017]

Judge, T. A., Cable, D. M., Bourdea, J. W., & Bretz, R. D. Jr. (1995). An empirical investigation of the predictors of executive career success. Personnel Psychology, 48(3), 485–519.

King, J. E., & Cooley, E. L. (1995). Achievement orientation and the impostor phenomenon among college students. Contemporary, Educational Psychology, 20(3), 304-312.

Kolligian, Jr., J., Sternberg, R. J. (1991). Perceived fraudulence in young adults: Is there an “imposter syndrome”? Journal of Personality Assessment , 56(2), 308-326.

Langford, J., & Clance, P. R. (1993). The imposter phenomenon: Recent research, findings regarding dynamics, personality and family patterns and their implications for treatment. Psychotherapy , 495-501.

Long, M. L., Jenkins, G. R., & Bracken, S. (2000, October). Impostors in the Sacred Grove: Working class women in the academe [70 paragraphs]. The Qualitative Report [On -line serial], (3/4). Available: http://www.nova.edu/ssss/QR/QR5-3/long.html

Mattie, C., Gietzen, J., Davis, S., & Prata, J., (2008). The imposter phenomenon: Self -assessment and competency to perform as a physician assistant in the United States. The Journal of Physician Assistant Education , 19(1), 5-12.

McDevitt, N. (2006, May 18). Unmasking the impostor phenomenon: Fear of failure paralyzes students and faculty. The McGill Reporter , 38(17), 1-2.

Neureiter M., Traut-Mattausch E. (2016). An inner barrier to career development: preconditions of the impostor phenomenon and consequences for career development. Front. Psychol. 7:48

Parkman, A. (2016). The impostor phenomenon in higher education: Incidence and impact. Journal of Higher

Education Theory and Practice. 16(1), 51-60.

Rottinghaus, P.J., Day, S.X., & Borgen, F.H. (2005). The Career Futures Inventory: A measure of career-related adaptability and optimism. Journal of Career Assessment , 13, 3-24.

Rottinghaus, P. J., Buelow, K. L., Matyja, A., & Schneider, M. R. (2012). The Career Futures Inventory Revised: Measuring Dimensions of Career Adaptability. Journal of Career Assessment , 20 (2), 123-139.

Sakulku, J. & Alexander, J. (2011). The Impostor Phenomenon. International Journal of Behavioral Science , 6(1), 73-92.

Thompson, T., Davis, H., & Davidson, J. (1998). Attributional and affective responses of imposters to academic success and failure outcomes. Personality and Individual Differences , 25(2), 381-396.

Vergauwe J., Wille B., Feys M., De Fruyt F., Anseel F. (2015). Fear of being exposed: the trait-relatedness of the impostor phenomenon and its relevance in the work context. Journal of Business Psychology , 30, 565–581.