|

Dr. Asif Mahmood, Tahmina Ayub, Dr Ibrahim Abdullah, Muddassar Sarfraz Institute of Business & Management, UniversityofEngineeringandTechnology, Lahore, Pakistan, Email; mahmood.engineer@gmail.com Department of Management and Sciences, COMSATS Institute of Information & Technology Lahore, Pakistan, Email: miabdullah@ciitlahore.edu.pk Hohai Business School, Hohai University, Nanjing, Jiangsu, PR China; Corresponding Author Email; muddassar@hhu.edu.cn , Phone # +86-18751861057 |

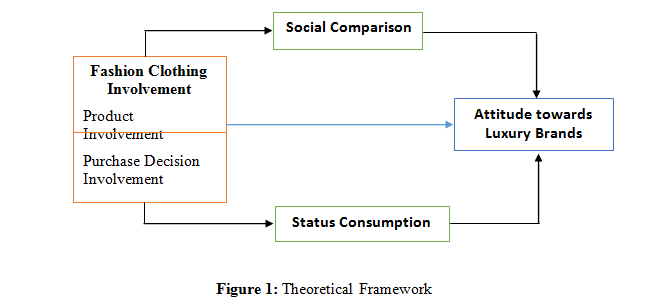

The purpose of this study is to examine the relationship between fashion clothing involvement (FCI) and the attitude towards luxury brands (ATLB), mediating role of social comparison (S_COM) and status consumption (S_CON). The study aims to expand the scope of fashion marketing research within the context of luxury clothing brand market. The paper opted for a descriptive study involving 251 respondents. Data were collected through online and offline survey methods. Structural equation modelling was employed to test the research hypotheses.

The study found that status consumption performs a partial mediating role on the relationship between FCI and ATLB. Non-probability sampling technique was used to collect the data. Due to lack of representation, the findings of this study cannot be projected or generalized beyond the sample unit used. The paper includes implications for market practitioners to effectively targetfashion-conscious consumers by developing marketing strategies that involves the element of attracting status consuming buyers. This paper extends the empirical model of FCI by incorporating fashion Clothing involvement as an antecedent of ATLB along with two mediators S_Com and S_Con.

The new era has undoubtedly made us witness of growth, technological advancement, economic development and progress in all manners of life. This growth has resulted not only in the formation of new phases in our life but also increased the complexities and challenges in the ways we perceive everything around us. One of the most demanding phenomena that have ever happened to this world is “Fashion” (FQ Qureshi, J Hashmi, Z Faisal, 2015).

Trend or style is the most commonly used terms to define fashion, which are often accepted in many societies at a time. Fashion includes many components and they vary for culture to culture like clothing, accessories, shoes, hand bags, cosmetics, hair styles or even cell phones in many countries; but the most commonly used component is clothing. Why there is a need for Fashion? People want to look good, attractive and acceptable in a society they live. Fashion describes a person’s taste and his desire to wear style. Clothing industry is considered as one of the most competitive and fastest growing industries where consumers’ taste, preferences and style change so rapidly (O’Cass, 2015). Clothing plays a vital role and a collection of functions in a person's life far beyond being a basic necessity only. (Emine, Fatma, 2016).

Fashion industry is one of the most growing segments in the economy . A very high number of designer brands have mushroomed in the last 10 years. A number of fashion design and textile institutes have also been established, and a keen interest in fashion and designer wear seems to define the consumption pattern, particularly among youth and most commonly in the urban cities (FQ Qureshi, J Hashmi, Z Faisal, 2015). The reason of choosing this particular industry is the growing trend of fashion among the people of our society.

Clothing industry is so immense and further categorized by different styles, taste, culture, class and fashion. It is rapidly changing over time making this complicated for the marketers to understand “why the consumers buy?” Despite of focusing on demographics there is a need to understand the psychological behavior of consumers towards clothing brands. If manufacturers and retailers of fashion apparel can identify target consumers’ preferences, they may be better able to attract and maintain their target consumer group (Rajagopal, 2011).

The purpose of this study is to increase the understanding of consumer psychology by testing the relationship between fashion clothing involvement and attitude towards luxury clothing brands under the mediating impact of consumers’ motives like status consumption and social comparison. Evidence of these relationships could help the marketers of clothing brands to better understand the influence of these motivators on consumers’ perceptions and their buying behaviors.

2.1 Fashion Clothing Involvement

Involvement can be described as the perceived importance of any good to a consumer, based on his needs, values and interests (Summers, Belleau, Xu, 2006; Kim, 2005; Solomon and Rabolt, 2004:119). Handa, Khare (2013) defines fashion clothing as a product to display one’s well-being and is considered to be an important factor of individual’s life. Fashion clothing involvement can be referred to as an extent to which a consumer views clothes as central part of their lives (Hourigan & Bougoure, 2011; O’Cass 2003). Fashion clothing is a term generally used for all the items that a person acquires for his self and attach to the body.

According to Xo (2008), fashion clothing could be used to enhance individual’s self-image. Moreover, in previous studies it has been empirically found that a strong level of public self-consciousness is extremely related to fashion clothing involvement (Xu, 2008). Few empirical studies have also been done to find its role in the developing economies (Shukla et al., 2006; Zhang and Kim, 2013). More empirical studies need to be done in different countries like Indonesia where people are becoming brand conscious and fashion clothing is becoming an important part of society (Luvaas, 2013).

According to O’Cass (2016), clothing can fulfill number of functions beyond just providing warmth or protection. There is a need to understand how and why consumers are getting so much involved towards fashion clothing in a society. Being involved in fashion clothing is a perpetual interest in demonstrating the self to the world (Goldsmith, Flynn and Clark, 2012).

Fashion clothing involvement can be better described as “the degree to which an individual is aware of and concerned about appearing fashionable through wearing fashionable clothes”. FCI has two dimensions, one is product involvement and other is purchase decision involvement.Product Involvement (FCPI) as the name implies, refers to the level of concern a consumer has for a product in his life (Mittal and Lee, 1989; O’Cass, 2000). The level of interest that a consumer shows towards purchasing a product and throughout his decision making process in purchasing that product comes under Purchase decision involvement (FCIPDI), according to Mittal and Lee, (1989) and O’Cass (2000).

2.2 Attitude towards Luxury Brands

Luxury is a mixture of comfort, affluence, richness, enjoyment and is incomplete without a basic ingredient of gratification. Luxury brands are always linked with exclusiveness means to shut out all the other considerations. People who have excess of money, they can spend it on satisfying those needs and desires that are not even essential (Dietz, 2014). Luxury brands include those goods and services that are completely exclusive, possess best quality, extravagant, prestigious and most importantly non-essential.

Previous researches shows that people pursue fashion and own luxury products to gain the attention of others as a form of social connection (Potts, 2007). Such products or services involve emotional aspects like sensory pleasure, aesthetic beauty and attachment. Luxury goods are often consumed to show one’s wellbeing and self-pleasure such as status-seeking (C Fuchs, E Prandelli, M Schreier, DW Dahl, 2013). Individuals with low spending power are more focused towards counterfeit products and the copy of original products. They are also involved in fashion clothing and they take interest in designer brands that are not affordable to them so they look for their alternatives to portray their self-image (R Casidy, AN Nuryana, SRH Hati, 2015).

Luxury products are basically for pleasure seekers, who have enough money to buy them. Such kind of goods are hard to obtain and they are not only significant to the person who owns them but also valuable to others. (Wiedmann, Hennigs, &Siebels, 2009). In other words, luxury goods satisfy both the physical and emotional needs of consumer, they deliver esteem to the owner (Shukla, 2010; Vigneron & Johnson, 2004). ‘Attitude towards luxury brands’ refers to the inclination of consumers towards those goods or services that have a very high standard; goods that are not essential but consumers possess some kind of emotional attachment with them (Shukla, 2011; Wiedmann et al., 2009).

2.3 Social Comparison

Festinger (1954) gave the idea of social comparison in his theory in which he defined social comparison as a process through which individuals evaluate their own behavior, possessions, attitudes, material things, beliefs and living styles in comparison with others. Social comparison is further divided into two main categories. Upward and downward social comparison. When people evaluate themselves with the group of people who they think are better than them comes under the category of upward social comparison and when they evaluate themselves with the group of people who they believe are worse than them comes under the umbrella of downward social comparison. Every person, whether consciously or unconsciously, is constantly involved in social comparison (Noerhardiyanty, J Abraham, 2016). People are always exposed to new fashion trends and the information they get regarding other people from their social group or from media they relate it to their own style and appearance. In other words, they compare themselves to others whether within their own social group or with the advertising models (Corcoran, Crusius & Mussweiler, 2011). Every person in one way or the other continuously involves in social comparison, it includes clothing, shoes, hand bags, mobile phones, and gadgets even hair styles. The strength of comparison varies from person to person (Sarwono, 2011).

Marketers are now using several phenomena extracted from social comparison theory in their marketing campaigns like comparing one’s material possessions (Richins 1992), comparing a person’s physical attractiveness to advertising models (Martin and Kennedy 1993, 1994), and consumer delicacy towards social comparison information. Caring strongly about how others perceive them, consumers sensitive to social comparison are aware of and anxious about others’ reactions to them (Christina S. Simmers, R. Stephen Parker & Allen D. Schaefer, 2014).

2.4 Status Consumption

There is always certain group of people in a society, who love to show their material commodities to display their social status and prestige. Some researchers define social consumption as displaying the purchase and ownership of certain products, which depict their status and social position in a society (Gabriel and Lang, 2006). From the last few years, the level of consumer fortune has increased; they love to spend more and more in buying luxury goods to consume status (Hader, 2008). The motivation behind consuming status goods is not just the game of income; it is backed by inner motivational factors like desire to seek status and impulsive behavior of consumers that urge them to buy status products (JK Eastman, KL Eastman, 2015).

Many people wish to acquire status and prestige; they hold all the aces throughout their life to acquire it. Many consumers also wish to show their sense of self by acquiring certain luxury goods to show an image of what they are and to impersonate what they feel. It also helps them to show about the type of social linkages they wish to have (A Cronje, B Jacobs, 2016). Status consumers are more conscious about their achievements, hence, showing their accomplishment to others is important (I Phau,M Teah, J Chuah, 2015).No one wants to live alone, sense of belongingness to the people of society is always there and psychologically it satisfies the human nature (J Li, XA Zhang, G Sun, 2015). People try to copy their group members in order to be accepted as group member themselves. The consumption of fashion clothing is in fact a sign of a society that focusses on status (A O'Cass, V Siahtiri, 2014).

Previous researches suggest that the rationale behind status consumption could be external (Shukla, 2011), or internal (Wiedmann, Hennigs, &Siebels, 2009), or may be both (Dubois & Laurent, 1996; Vigernon & Johnson, 2004; Tsai, 2005; Truong et al., 2008; Kapferer&Bastien, 2009; Amatulli & Guido, 2012). External motives include interpersonal objectives that are social such as to show off your wealth (Vigneron& Johnson, 2004; Truong et al., 2008), to show your success to others or to represent yourself as elite (Mason, 2001; Truong et al, 2008; Han, Nunes, & Dreze, 2010). Whereas, internal motives are the personal intentions belonging to oneself (Truong et al., 2008), to seek pleasure (Hudders, 2012) or to get inner satisfaction by wearing the best quality (Vigneron & Johnson, 1999).

This study is entirely quantitative in nature and data were collected from respondents those are located in different areas. Young people’s role as innovators within the fashion context has been extensively cited in the literature (Bakewell et al., 2006; Hourigan and Bougoure, 2012; O’Cass and Choy, 2008). Convenience based sampling technique is employed to collect data. The selected sample size should be appropriate and competent to symbolize the population. In this study the sample size of 251 has been used to collect the data. All respondents’ age range was between 16 and 35 years. 114 representatives were female while 137 representatives were male. Similarly, 159 respondents were in the age group of 16-25 years, 88 in group of 26-35 and remaining 5 were in the group of above 35 years’ people.

Sample size was deduced from the previous researches related to fashion clothing involvement among youth (Goldsmith, Flynn & Clark, 2012; SR. Hourigan, US. Bougoure,2011; Correia, Branco, 2013). This study uses existing scales from the literature to measure the constructs. Fashion clothing involvement is measured through 11 items adapted from O’Cass (2000) in the form of two factor scale, product involvement and purchase decision involvement. Five items measure social comparison (Zhang and Kim, 2012; Vahid Nasehifar and Seyed Mohammad Sadiq, 2014). To measure status consumption, five items scale developed by Eastman et al. (1999) is used. Four items measure the attitude towards luxury brands based on Suntornpithug and Khamalah (2010); Zhan and He (2011) and Kim, H.K, Ko, Eunju, Bing Xu, Yoosun Han, (2012). Partial Least Squares – Structural Equation Modeling Technique (PLS-SEM) is applied as a statistical tool to study the desired relationship.

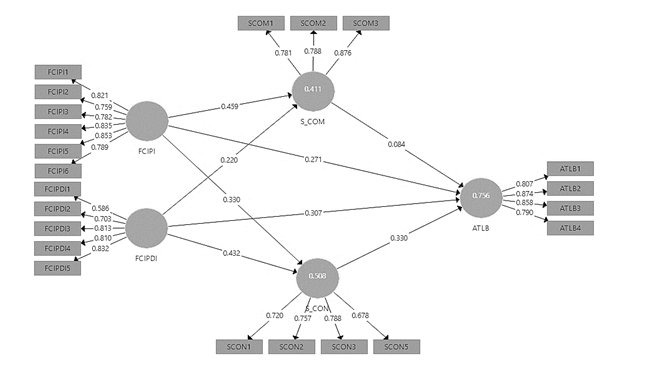

Initially component analysis was taken into consideration where the loading values which are greater than 0.6 have to be selected and considered (Chin, 1998). It is further explained that if latent variables are in the model the loadings 0.5 or outmost are acceptable at early stages of scale development.Construct validity is established with the help convergent and discriminant validity. It explains that how measurement items are linked with the construct. Convergent validity is confirmed by three tests; item reliability, composite reliability and average variance extracted (AVE).

Measurement model has been shown in the table 1. Loading values directs that which indicators should be considered or not. So the items which were not fulfilling the criteria of loading values were eliminated. Reliability of the constructs with the help of loading values tells about the consistency of the results.

3.1 Hypothesis Development

H1: FCIPI is positively correlated with ATLB

H2: FCIPDI is positively correlated with ATLB

H3: FCIPI is positivelycorrelated with S_COM

H4: FCIPI is positively correlated with S_CON

H5: FCIPDI is positively correlated with S_COM

H6: FCIPDI is positivelycorrelated with S_CON

H7: S_COM is positivelycorrelated with ATLB

H8: S_CON is positivelycorrelated with ATLB

H9: S_COM mediates relationship between FCIPI and ATLB

H10: S_COM mediates relationship between FCIPDI and ATLB

H11: S_CON mediates relationship between FCIPI and ATLB

H12: S_CON mediates relationship between FCIPDI and ATLB

The indicators having value greater than 0.5 were considered as shown in the figure below.

PLS is a non-parametric test and in order to get good result and for the continuation of significant tests, boot strapping were proceeded.

Table 1: Measurement Model

|

Constructs |

Measurement Items |

Loading Value |

Cronbach’s Alpha |

Composite Reliability |

AVE |

|

Fashion Clothing Involvement: Product Involvement (FCIPI) |

FCIPI1 FCIPI2 FCIPI3 FCIPI4 FCIPI5 FCIPI6 |

0.821 0.759 0.782 0.835 0.853 0.789

|

0.892

|

0.918 |

0.651 |

|

Fashion Clothing Involvement: Purchase Decision Involvement (FCIPDI) |

FCIPDI1 FCIPDI2 FCIPDI3 FCIPDI4 FCIPDI5 |

0.586 0.703 0.813 0.810 0.832 |

0.806

|

0.867 |

0.569 |

|

Social Comparison (S_Com) |

S_Com1 S_Com2 S_Com3 |

0.781 0.788 0.876 |

0.748 |

0.857 |

0.666 |

|

Status Consumption (S_Con) |

S_Con1 S_Con2 S_Con3 S_Con5 |

0.720 0.757 0.788 0.678 |

0.719 |

0.826 |

0.543 |

|

Attitude Towards Luxury Brands (ATLB)

|

ATLB1 ATLB2 ATLB3 ATLB4 |

0.807 0.874 0.858 0.790 |

0.853 |

0.901 |

0.694 |

Note: Some observable items of constructs including S_Com4, S_Com5 and S-Con4 were deleted from the initial model analysis because of their factor loading values lower than 0.5. (P< 0.05)

Values of Cronbach alpha above 0.7 are showing and confirming the reliability of the constructs. In next column composite reliability (CR) is shown. Furthermore, average variance extracted (AVE) has been shown in last column which tells about the actuality of the convergent validity (convergent validity is a type of validity which serves as a measure to find that the theoretical inter-relationship of the indicators actually exists). AVE explains that how value of variance in a construct with respect to its relative items to amount of variation that existed because of measurement error. Hence, AVE values for Fashion Clothing Involvement: Product Involvement, Fashion Clothing Involvement: Purchase Decision Involvement, Social Comparison, Status Consumption and Attitude towards Luxury Brands are 0.651, 0.569, 0.666, 0.543 and 0.694 respectively which are all in acceptable range as 0.5. So, it is concluded that each constructs have acceptable convergent validity.

The values of Discriminant validity for Attitude towards Luxury Brands, Fashion Clothing Involvement: Purchase Decision Involvement, Fashion Clothing Involvement: Product Involvement, Social Comparison and Status Consumption are 0.833, 0.754, 0.807, 0.816, 0.737 respectively.

Furthermore, discriminant validity is also determined by cross loading values. The outcomes of both the tests indicate there is significant presence of discriminant validity among all variables grounded on the evidence of cross loading and diagonal square root value of AVE criterion. Values of Cronbach alpha and composite reliability above 0.7 are showing and confirming the reliability of each selected construct. Factor loading values are greater than 0.6, AVE values for all the constructs are in acceptable range as 0.5. So, it is concluded that each construct has acceptable convergent validity. There is significant presence of discriminant validity among all variables grounded on the evidence of cross loading and diagonal square root value of AVE criterion.

Table 2: Hypothesis Testing—Direct Effects

|

Relationships Hypothesis |

Path Coefficients |

Sample Mean |

Standard Error |

T-Statistics |

P-Value |

Accepted/ Rejected |

|

FCIPI -> ATLB |

0.419 |

0.421 |

0.097 |

4.339 |

0.000 |

Accepted |

|

FCIPDI -> ATLB |

0.468 |

0.468 |

0.101 |

4.624 |

0.000 |

Accepted |

|

FCIPI -> S_COM |

0.459 |

0.456 |

0.110 |

4.167 |

0.000 |

Accepted |

|

FCIPDI -> S_COM |

0.220 |

0.229 |

0.123 |

1.789 |

0.073 |

Accepted |

|

S_COM -> ATLB |

0.084 |

0.093 |

0.078 |

1.081 |

0.280 |

Rejected |

|

FCIPI -> S_CON |

0.330 |

0.329 |

0.115 |

2.869 |

0.004 |

Accepted |

|

FCIPDI -> S_CON |

0.432 |

0.440 |

0.118 |

3.660 |

0.000 |

Accepted |

|

S_CON -> ATLB |

0.330 |

0.321 |

0.076 |

4.369 |

0.000 |

Accepted |

ß Coefficient Value should be more than 0.2 (Hildebrand, 1986)

P Value should be less than 0.05 (Neyman-Pearson, 1966)

The causal relationship can be found in the model and it is empirically supported. Fashion Clothing Involvement: Product Involvement, Fashion Clothing Involvement: Purchase Decision Involvement, Social Comparison, Status Consumption positively influenced each other and also caused consumers’ attitude towards Luxury Brands directly and with mediator. The path should be at or above 0.2 is ideally which can be found in the table, similarly, T-statistics is showing significant values and direction is consistent with expectations. The direct path (Without Mediator) between FCIPI and ATLB is highly significant (β= 0.419, T-Value =4.339, p < 0.05) which supports H1. Similarly, direct path (Without Mediator) between FCIPDI and ATLB is also found highly significant (β=0.468, T-value =4.624 p < 0.05) which fully supports H2. The direct Path analysis with Mediator, the path between FCIPI and SCOM is highly significant (β=0.459, T-Value = 4.167 p < 0.05) which fully supports H3. The direct path between FCIPDI and SCOM is slightly significant (β=0.220, T-Value = 1.798 p < 0.073) which supports H4 at 10% Confidence interval. The direct path between SCOM and ATLB is insignificant as (β=0.084 T-Value= 1.081, p > 0.05) thus does not supporting H5. The direct path between FCIPI and SCON is significant (β=0.330, T-value= 2.869, p < 0.05) thus supporting H6. The direct path between FCIPDI and SCON is significant (β=0.432, T-Value= 3.660 p < 0.05) thus supporting H7. The direct path between SCON and ATLB is highly significant (β=0.330, T-value = 4.369 p < 0.05) which fully supports H8.

Table 3: Hypothesis Testing - Indirect or Mediation Effect

|

Bootstrapped Confidence Interval |

|

|||||||||

|

|

Path a |

Path b |

Indirect Effect |

SE |

t-value |

95% LL |

95% UL |

Accepted/ Rejected |

||

|

FCIPI -> S_COM->ATLB |

0.46 |

0.08 |

0.04 |

0.04 |

1.08 |

-0.03 |

0.11 |

Rejected |

||

|

FCIPDI -> S_COM->ATLB |

0.22 |

0.08 |

0.02 |

0.05 |

0.37 |

-0.08 |

0.12 |

Rejected |

||

|

FCIPI -> S_CON->ATLB |

0.33 |

0.33 |

0.11 |

0.06 |

1.98 |

0.01 |

0.22 |

Accepted |

||

|

FCIPDI -> S_CON->ATLB |

0.43 |

0.33 |

0.14 |

0.05 |

2.69 |

0.04 |

0.25 |

Accepted |

||

Source: Researcher’s calculations.

T- Value should be greater than 1.96 (Sobel, 1982)

To investigate the significance of mediation and further to check whether the presence of mediation is full, partial or no mediation; researcher used Bootstrapped Confidence Interval Sobel Test. The output of the Mediation Effect (table 3) shows that the first mediator variable (Social Comparison) insignificantly mediate the effect of Fashion Clothing Involvement: Product Involvement (independent variable) to Attitude towards Luxury Brands (dependent variable) as the Sobel test statistic value is 1.08 lower than 1.96 and corresponding there lies a Zero value in between the lower limit (-0.03) and upper limit (0.11) of bootstrapped confidence interval. Which mean such mediation is insignificant and no mediation. Similarly, first mediator variable (Social Comparison) insignificantly mediate the effect of Fashion Clothing Involvement: Purchase Decision Involvement (independent variable) to Attitude towards Luxury Brands (dependent variable) as the Sobel test statistic value is 0.37 lower than 1.96 and corresponding there lies a Zero value in between the lower limit (-0.08) and upper limit (0.18) of bootstrapped confidence interval. Which mean such mediation is insignificant and no mediation.So the hypothesis H9 and H10 are rejected.

Product Involvement (independent variable) to Attitude towards Luxury Brands (dependent variable) as the Sobel test statistic value is 1.98 higher than 1.96 and corresponding there does not lies a Zero value in between the lower limit (0.01) and upper limit (0.22) of bootstrapped confidence interval. Which mean such mediation is significant and partial mediation as the path coefficient of direct effect is higher as compared to path coefficient with mediation effect but t-statistic is significant. Similarly, second mediator variable (Status Consumption) also significantly mediate the effect of Fashion Clothing Involvement: Purchase Decision Involvement (independent variable) to Attitude towards Luxury Brands (dependent variable) as the Sobel test statistic value is 2.69 higher than 1.96 and corresponding there does not lies a Zero value in between the lower limit (0.04) and upper limit (0.25) of bootstrapped confidence interval. Which mean such mediation is significant and partial mediation as the path coefficient of direct effect is higher as compared to path coefficient with mediation effect but t-statistic is significant resulting in the acceptation of H11 and H 12.

Hence in present study conceptual framework first mediator (social comparison) has insignificant mediation effect on the relationship between independent and dependent variables but the mediator (Status Consumption) has significant mediation effect on the relationship between independent and dependent variables.

Table 2: Hypothesis Testing—Direct Effects

|

Relationships Hypothesis |

Path Coefficients |

Sample Mean |

Standard Error |

T-Statistics |

P-Value |

Accepted/ Rejected |

|

FCIPI -> ATLB |

0.419 |

0.421 |

0.097 |

4.339 |

0.000 |

Accepted |

|

FCIPDI -> ATLB |

0.468 |

0.468 |

0.101 |

4.624 |

0.000 |

Accepted |

|

FCIPI -> S_COM |

0.459 |

0.456 |

0.110 |

4.167 |

0.000 |

Accepted |

|

FCIPDI -> S_COM |

0.220 |

0.229 |

0.123 |

1.789 |

0.073 |

Accepted |

|

S_COM -> ATLB |

0.084 |

0.093 |

0.078 |

1.081 |

0.280 |

Rejected |

|

FCIPI -> S_CON |

0.330 |

0.329 |

0.115 |

2.869 |

0.004 |

Accepted |

|

FCIPDI -> S_CON |

0.432 |

0.440 |

0.118 |

3.660 |

0.000 |

Accepted |

|

S_CON -> ATLB |

0.330 |

0.321 |

0.076 |

4.369 |

0.000 |

Accepted |

ß Coefficient Value should be more than 0.2 (Hildebrand, 1986)

P Value should be less than 0.05 (Neyman-Pearson, 1966)

The causal relationship can be found in the model and it is empirically supported. Fashion Clothing Involvement: Product Involvement, Fashion Clothing Involvement: Purchase Decision Involvement, Social Comparison, Status Consumption positively influenced each other and also caused consumers’ attitude towards Luxury Brands directly and with mediator. The path should be at or above 0.2 is ideally which can be found in the table, similarly, T-statistics is showing significant values and direction is consistent with expectations. The direct path (Without Mediator) between FCIPI and ATLB is highly significant (β= 0.419, T-Value =4.339, p < 0.05) which supports H1. Similarly, direct path (Without Mediator) between FCIPDI and ATLB is also found highly significant (β=0.468, T-value =4.624 p < 0.05) which fully supports H2. The direct Path analysis with Mediator, the path between FCIPI and SCOM is highly significant (β=0.459, T-Value = 4.167 p < 0.05) which fully supports H3. The direct path between FCIPDI and SCOM is slightly significant (β=0.220, T-Value = 1.798 p < 0.073) which supports H4 at 10% Confidence interval. The direct path between SCOM and ATLB is insignificant as (β=0.084 T-Value= 1.081, p > 0.05) thus does not supporting H5. The direct path between FCIPI and SCON is significant (β=0.330, T-value= 2.869, p < 0.05) thus supporting H6. The direct path between FCIPDI and SCON is significant (β=0.432, T-Value= 3.660 p < 0.05) thus supporting H7. The direct path between SCON and ATLB is highly significant (β=0.330, T-value = 4.369 p < 0.05) which fully supports H8.

Table 3: Hypothesis Testing - Indirect or Mediation Effect

|

Bootstrapped Confidence Interval |

|

|||||||||

|

|

Path a |

Path b |

Indirect Effect |

SE |

t-value |

95% LL |

95% UL |

Accepted/ Rejected |

||

|

FCIPI -> S_COM->ATLB |

0.46 |

0.08 |

0.04 |

0.04 |

1.08 |

-0.03 |

0.11 |

Rejected |

||

|

FCIPDI -> S_COM->ATLB |

0.22 |

0.08 |

0.02 |

0.05 |

0.37 |

-0.08 |

0.12 |

Rejected |

||

|

FCIPI -> S_CON->ATLB |

0.33 |

0.33 |

0.11 |

0.06 |

1.98 |

0.01 |

0.22 |

Accepted |

||

|

FCIPDI -> S_CON->ATLB |

0.43 |

0.33 |

0.14 |

0.05 |

2.69 |

0.04 |

0.25 |

Accepted |

||

Source: Researcher’s calculations.

T- Value should be greater than 1.96 (Sobel, 1982)

To investigate the significance of mediation and further to check whether the presence of mediation is full, partial or no mediation; researcher used Bootstrapped Confidence Interval Sobel Test. The output of the Mediation Effect (table 3) shows that the first mediator variable (Social Comparison) insignificantly mediate the effect of Fashion Clothing Involvement: Product Involvement (independent variable) to Attitude towards Luxury Brands (dependent variable) as the Sobel test statistic value is 1.08 lower than 1.96 and corresponding there lies a Zero value in between the lower limit (-0.03) and upper limit (0.11) of bootstrapped confidence interval. Which mean such mediation is insignificant and no mediation. Similarly, first mediator variable (Social Comparison) insignificantly mediate the effect of Fashion Clothing Involvement: Purchase Decision Involvement (independent variable) to Attitude towards Luxury Brands (dependent variable) as the Sobel test statistic value is 0.37 lower than 1.96 and corresponding there lies a Zero value in between the lower limit (-0.08) and upper limit (0.18) of bootstrapped confidence interval. Which mean such mediation is insignificant and no mediation.So the hypothesis H9 and H10 are rejected.

Product Involvement (independent variable) to Attitude towards Luxury Brands (dependent variable) as the Sobel test statistic value is 1.98 higher than 1.96 and corresponding there does not lies a Zero value in between the lower limit (0.01) and upper limit (0.22) of bootstrapped confidence interval. Which mean such mediation is significant and partial mediation as the path coefficient of direct effect is higher as compared to path coefficient with mediation effect but t-statistic is significant. Similarly, second mediator variable (Status Consumption) also significantly mediate the effect of Fashion Clothing Involvement: Purchase Decision Involvement (independent variable) to Attitude towards Luxury Brands (dependent variable) as the Sobel test statistic value is 2.69 higher than 1.96 and corresponding there does not lies a Zero value in between the lower limit (0.04) and upper limit (0.25) of bootstrapped confidence interval. Which mean such mediation is significant and partial mediation as the path coefficient of direct effect is higher as compared to path coefficient with mediation effect but t-statistic is significant resulting in the acceptation of H11 and H 12.

Hence in present study conceptual framework first mediator (social comparison) has insignificant mediation effect on the relationship between independent and dependent variables but the mediator (Status Consumption) has significant mediation effect on the relationship between independent and dependent variables.

Table 4: Model Goodness of Fit (GOF)

|

Constructs |

Communality/ AVE |

R2 |

SRMR |

|

ATLB |

0.694 |

0.756 |

|

|

FCIPDI |

0.569 |

0.0000 |

|

|

FCIPI |

0.651 |

0.0000 |

|

|

S_COM |

0.666 |

0.411 |

|

|

S_CON |

0.543 |

0.508 |

|

|

Average Scores |

0.6246 |

0.8169 |

|

|

Communality * Redundancy |

0.3487 |

0.067 |

|

|

GOF= Ö (AVE * R2) |

0.5905 |

|

|

R-Square Values ≥ 0.3 (Hoffmann and Brinbrich, 2012) SRMR ≥ 0.05 and ≤ 0.08

As PLS does not generate overall goodness of fit indices, the R2 is the primary way to evaluate the explanatory power of the model (Wasko & Faraj, 2005). However, another diagnostic tool is presented by Tenenhaus, Vinz, Chatelin & lauro (2005) to assess the model fit is known as goodness of fit (GOF) index. The GOF measure uses the geometric mean of the average communality or AVE and average R2 (for endogenous constructs). Hoffmann and Brinbrich (2012) report the following cut-off values for assessing the results of DOF analysis: GOF small = 0.1; GOF medium = 0.25; GOF large + 0.36. For present study the value of GOF index expressed in table 5 is 0.5905. Which indicate the model used in this study is very good fit. Goodness of fit is also determined with the SRMR value if it is between 0.05 to 0.08 and in this study it is 0.067.

This study has extended the body of literature on the role of social comparison and status consumption in fashion context through an examination of the relationship between FCI, ATLB of consumers. This study involves both the direct and indirect relation of fashion clothing involvement and the attitude of consumers towards luxury brands.

First, this study found a significant relationship between Fashion Clothing Involvement and ATLB, which shows that consumers who are involved in fashion clothing they tend to be attracted towards luxury clothing brands also. Second, this study found out that the extent of individuals towards luxury brands could also be affected by some psychological behaviors like social comparison or status consumption. The results of this study show, people are significantly influenced by the drive of status consumption.

The theoretical implication of this study involves the impact of two individual motives S_COM and S_CON on the consumption behaviors of consumers, particularly in clothing sector. According to the results, status consumption influences the youth to get attracted towards luxury clothing brands. More personality traits could be studied to measure their impacts on people’s attitude towards luxury brands.

This study can help the market practitioners to understand how status consumption could be a useful source of attracting consumers towards luxury brands because it is a strong motive from which people may expect to derive happiness while purchasing luxury clothing products. Marketer practitioners will be better able to produce advertising messages that target such consumers who are status conscious. People, driven by status consumption want to show their sense of self to others by acquiring those goods and services that are luxurious.

4.1 Limitations and future research

This study has several limitations which can be addressed in future research. Study can be done across different societies. Due to non-probability sampling technique used to collect the data its lack of representation and its exploratory nature, the findings of the study cannot be projected or generalized beyond the sample unit used.

Future researches could examine various other psychological characteristics or personality traits that can play the mediating roles between fashion clothing involvement and the attitude towards luxury brands. Despite of just focusing on this general term “Clothing”, specific brands can be studied through this model. Due to cultural differences, their consumption patterns may be different.

Ali, F., & Amin, M. (2014). The effect of physical environment on customer’s emotions, satisfaction and behavioral loyalty, Journal for Global Business Advancement. 7(3), 249-266

Amatulli, C. and G. Guido (2012), “Externalised vs. Internalised Consumption of Luxury Goods: Propositions and Implications for Luxury Retail Marketing,” The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research, 22 (2), 189-207.

Bakewell, C., Mitchell, V.W, Rothwell, M. (2006), “UK Generation Y male fashion consciousness”, Journal of Fashion Marketing & Management, Vol. 10 No. 2, pp. 169-180.

Bandura, A. (1991), “Social cognitive theory of self-regulation”, Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, Vol. 50 No. 2, pp. 248-287.

Banister, EN and Hogg, MK (2004), “Negative symbolic consumption and consumers' drive for self-esteem”, European Journal of Marketing, vol. 38, no. 7, pp. 850-868

Birkinshaw, J., Morrison, A., &Hulland, J. (1995). Structural and competitive determinants global integration strategy. Strategic Management Journal, 16(8), 637-655.

Casidy, R., Nuryana, A. N., &Hati, S. R. H. (2015). Linking fashion consciousness with Gen Y attitude towards prestige brands. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 27(3), 406-420.

Chin, W. W. (1998). The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. In

Corcoran, Katja, Jan Crusius& Thomas Mussweiler. (2011). “Social Comparison: Motives, Standards, and Mechanisms” in Derek Chadee [ed]. Theories in Social Psychology. Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell, pp.119-139.

Cramer, D. & Howitt, D. (2004) The SAGE dictionary of statistics. London: SAGE

Cronje, A., Jacobs, B., & Retief, A. (2016). Black urban consumers’ status consumption of clothing brands in the emerging South African market. International Journal of Consumer Studies.

De Klerk, H. M., &Magwaza, N. N. (2015). Young females' body image clothing involvement and appearance management.

Dittmar, H. (1992), The Social Psychology of material possessions, St. Martin’s Press, New York, NY.

Danziger, P. (2004). Let them eat cake: Marketing luxury to the masses-as well as the classes. Dearborn trade publishing.

Doane, D. P. &Sewad, L.E. (2011) Measuring Skewness. Journal of Statistic Education, 19 (2), 1-18.

Dubois, B. and G. Laurent. (1996), “The Functions of Luxury: A Situational Approach to Excursionism,” Advances in Consumer Research, 23, 470-477.

Eastman, J.K., Goldsmith, R.E. and Flynn, L.R. (1999), “Status consumption in consumer behavior: scale development and validation”, Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, Vol. 7 No. 3, pp. 41-52.

Eastman, J. K., & Eastman, K. L. (2015). Conceptualizing a Model of Status Consumption Theory: An Exploration of the Antecedents and Consequences of the Motivation to Consume for Status. Marketing Management

EmineKoca, FatmaKoc (2016), “Study of Clothing Purchasing Behavior by Gender with Respect to Fashion and Brand Awareness”, European Scientific Journal March 2016 edition vol.12, No.7 ISSN: 1857 – 7881 (Print) e - ISSN 1857- 7431

Fenigstein, A. (1979), “Self-consciousness, self-attention, and social interaction”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 37 No. 1, pp. 75-86.

Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of Social Comparison Processes. Human Relations, 7, 117-170.

Fornell, C., &Larcker, D.F., (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39-50.

Fuchs, C., Prandelli, E., Schreier, M., & Dahl, D. W. (2013). All that is users might not be gold: How labeling products as user designed backfires in the context of luxury fashion brands. Journal of Marketing, 77(5), 75-91.

Gabriel, Y and Lang, T (2006), The Unmanageable Consumer, 2nd ed., Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA.

Gilbert, Paul. (2000). “The Relationship of Shame, Social Anxiety, and Depression: The Role of the Evaluation of Social Rank” in Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 7(3), pp.174-189

Hader, S. (2008), “Wooing Luxury Brands”, Marketing Management, Vol.17 No.4, pp. 27-31

Han, Y.J., J.C. Nunes, and X. Dreze (2010), “Signaling Status With Luxury Goods: The Role of Brand Prominence,” Journal of Marketing, 74, 15-30.

Heine, K.: (2011), Das deutsche Luxus-Wunder, Luxury Business Day, Munich.

Heine, K. (2012). The concept of luxury brands.Luxury brand management, 1, 2193-1208.

Hoffmann, A. &Birnbrich, C. (2012). The impact of fraud prevention on bank-customer relationships: An empirical investigation in retail banking. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 30(5), 390-407.

Hourigan, S. R., &Bougoure, U. S. (2012). Towards a better understanding of fashion clothing involvement. Australasian Marketing Journal (AMJ), 20 (2), 127-135.

Hudders, L. (2012), “Why the Devil Wears Prada: Consumers’ Purchase Motives for Luxuries,” Journal of Brand Management, 19 (7), 609-622,

Janis Dietz, (2014) "The Luxury Strategy: Break the Rules of Marketing to Build Luxury Brands. 2e", Journal of Product & Brand Management, Vol. 23 Issue: 3, pp. 244 – 245

Kapferer, J.N. and V. Bastien (2009), “The Specificity of Luxury Management: Turning Marketing Upside Down,” Brand Management, 16, (5/6), 311-322.

Kapferer, J.-N.: (2008), The new strategic brand management, 4 edn, London.

Kasser, T. (2012), The High Price of Materialism, The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

Kim, H. S. (2005). Consumer profiles of apparel product involvement and values. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal, 9(2), 207-220.

Li, J., Zhang, X. A., & Sun, G. (2015). Effects of “Face” Consciousness on Status Consumption among Chinese Consumers: Perceived Social Value as a Mediator. Psychological reports, 116(1), 280-291.

Luvaas, B. (2013), “Indonesian fashion blogs: on the promotional subject of personal style”, Fashion Theory: The Journal of Dress, Body & Culture, Vol. 17 No. 1, pp. 55-76.

Martin, Mary C. and Patricia F. Kennedy (1993), "Advertising and Social Comparison: Consequences for Female Preadolescents and Adolescents," Psychology and Marketing, 10 (November/December), forthcoming.

Martin, Mary C. and Patricia F. Kennedy (1994), "The Measurement of Social Comparison to Advertising Models: A Gender Gap Revealed," Gender and Consumer Behavior, Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications, forthcoming.

Mary C. Martin and Patricia F. Kennedy (1994),"Social Comparison and the Beauty of Advertising Models: the Role of Motives For Comparison", in NA -Advances in Consumer Research Volume 21, eds. Chris T. Allen and Deborah Roedder John, Provo, UT: Association for Consumer Research, Pages: 365-371.

Mason, R.S. (2001), “Conspicuous Consumption: A Literature Review,” European Journal of Marketing, 18 (3), 26-39.

Noerhardiyanty, Y., & Abraham, J. (2016). Social Comparison as a Predictor of Shame Proneness Dimensions. SOSIOHUMANIKA, 8(2).

O’Cass, A. (2000). An assessment of consumers’ product, purchase decision, advertising and consumption involvement in fashion clothing. Journal of Economic Psychology, 21(5), 545-576.

O' Cass, A. (2004). “Fashion clothing consumption: antecedents and consequences of fashion clothing involvement”, European Journal of Marketing, vol. 38, no. 7, pp. 869-882.

O’Cass, A. Thomas Muller (2015), “ A Study of Australian Materialistic Values, Product Involvement and the Self-Image/ Product-Image Congruency Relationships for Fashion Clothing,” Global Perspectives in Marketing for the 21st Century, Part of the series Developments in Marketing Science: Proceedings of the Academy of Marketing Science pp 400-402

O’Cass, A. (2016), “An assessment of consumers’ product, purchase decision, advertising decision and consumption involvement in fashion clothing”, Journal of economic psychology, Vol.21 pp. 545-76

O’Cass, A. and Choy, E. (2008), “Studying Chinese Generation Y consumers’ involvement in fashion clothing and perceived brand status”, Journal of Product & Brand Management,Vol. 17 No. 5, pp. 341-352.

O’Cass, A., &Siahtiri, V. (2014). Are young adult Chinese status and fashion clothing brand conscious? Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 18(3), 284-300.

Parker, RS, Hermans, CM and Schaefer, AD (2004), “Fashion consciousness of Chinese, Japanese and American teenagers”, Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 176-186.

Peluchette, JV, Karl, K and Rust, K (2006), “Dressing to impress: beliefs and attitudes regarding workplace attire”, Journal of Business and Psychology, vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 45-63.

Pentecost, R and Andrews, L (2010), “Fashion retailing and the bottom line: the effects of the generational cohort, gender, fashion fanship, attitudes and impulse buying on fashion expenditure”, The Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 43-52.

Phau, I., Teah, M., &Chuah, J. (2015). Consumer attitudes towards luxury fashion apparel made in sweatshops. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 19(2), 169-187.

Piacentini, M. and Mailer, G. (2004), “Symbolic consumption in teenagers’ clothing choices”, Journal of Consumer Behaviour, Vol. 3 No. 3, pp. 251-262.

Potts Jason (2007) “Fashionomics. Policy”, A Journal of Public Policy and Ideas, Vol: 23, Issue 4, pp. 10-15

Quoquab, F., Yasin, N.M. and Dardak, R.A. (2014), “A qualitative inquiry of multi-brand loyalty: some propositions and implications for mobile phone service providers”, Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, Vol. 26 No. 2, pp. 250-271.

Qureshi, F. Q., Hashmi, J., & Faisal, Z. (2015). The Impact of Gender, Income and Occupation on Fashion Consciousness.World,5(2).

Rajagopal. (2011). Consumer culture and purchase intentions toward fashion apparel in Mexico. Journal of Database Marketing & Customer Strategy Management, 18, 286–307.

Razali, N.M. &Wah, Y.B. (2011). Power comparison of Shapiro- Wilk, Kolmogorov-Smirnov, Lilliefors and Anderson-Darling tests. Journal of Statistic Modeling and Analytics, 2(1), 21-33.

Ronald E. Goldsmith, Leisa R. Flynn and Ronald A. Clark (2012), “Materialistic, Brand Engaged and Status Consuming Consumers and Clothing Behaviors”, Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, Vol 16 No.1, 2012, pp. 102-119.

Richins, Marsha L. (1992), "Media Images, Materialism, and What Ought to Be: The Role of Social Comparison," in Meaning, Measure, and Morality of Materialism, eds. F. Rudmin and M. Richins, Kingston, Ontario: Research Workshop on Materialism and Other Consumption Orientations, 202-206.

Richins, M.L. (2014), “The material values scale: measurement properties and development of a short form”, Journal of Consumer Research, Vol.31 No.1, pp. 209-19.

Roberts, J.A. and Jones, E. (2001), Money attitudes, credit card use, and compulsive buying among American college students”, Journal of Consumer Affairs, Vol.35 No. 2, pp. 213-40

Sarwono, S. (2011). Teori-teoriPsikologiSosial. Jakarta: RajaGrafindoPersada.

Shapiro, S.S. & Wilk, M.B (1965). An Analysis of variance Test for Normality (Complete Sample). Biometrika, 52(3/4), 591-611

Shukla, P., Jin, Z., Chansarkar, B. and Kondap, N.M. (2006), “Brand origin in an emerging market: perceptions of Indian consumers”, Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics,Vol. 18 No. 4, pp. 283-302.

Shukla P. (2010), Status consumption in cross-national context: socio-psychological, brand and situational antecedents. International Marketing Review 2010; 27(1):108–29.

Shukla, P. (2011), “Impact of Interpersonal Influences, Brand Origin and Brand Image on Luxury

Purchase Intentions: Measuring Interfunctional Interactions and a Cross-National Comparison,” Journal of World Business, 46, 242-252.

Shukla, P., &Purani, K. (2012). Comparing the importance of luxury value perceptions in cross-national contexts. Journal of Business Research, 65(10), 1417-1424.

Solomon, M.R. &Rabolt, N.J. 2004. "Consumer behaviour in fashion. New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Simmers, C. S., Parker, R. S., & Schaefer, A. D. (2014). The importance of fashion: The Chinese and US Gen Y perspective. Journal of Global Marketing, 27(2), 94-105

Sproles, G. B. (1981). “Analyzing fashion life cycles: principles and perspectives”, The Journal of Marketing, vol. 45, no. 4, pp. 116-124.

Summers, T. A., Belleau, B. D., & Xu, Y. (2006). Predicting purchase intention of a controversial luxury apparel product. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal, 10(4), 405-419.

Suntornpithug, N. Khamalah, J, .2010. Machine and person interactivity: the driving forces behind influences on consumer’s willingness to purchase online. J. Electron.Com. Res. 11 (4), 299-325.

Surienty, L., Ramayah, T., Lo, M., C., Tarmizi, A., N., (2013). Quality of Work-life and Turnover Intention: A Partial Least Square (PLS) Approach. Springer Science + management Dordreht, DOI 10. 1007/s 11205-0130486-5

Tenenhaus, M., Vinzi, V., Chatelin, Y. M. &Lauro, C. (2005). PLS path modelling. Computational Statistics and Data Analysis, 48(1), 159-205.

Thompson, C. J., &Haytko, D. L. (1997). “Speaking of fashion: consumers' uses of fashion discourses and the appropriation of countervailing cultural meanings”. Journal of consumer research, 24(1), 15-42.

Truong, Y., Simmons, G., McColl, R., and Kitchen, P.J. (2008),” Status and Conspicuousness – Are They Related? Strategic Marketing Implications for Luxury Brands,” Journal of Strategic Marketing, July, Vol. 16 No. 3, pp. 189-203.

Tsai, S. (2005), “Impact of Personal Orientation on Luxury-Brand Purchase Value: An International Investigation,” International Journal of Market Research, 47 (4), 429-454.

Uy, T., Yi, K. M., & Zhang, J. (2013). Structural change in an open economy. Journal of Monetary Economics, 60(6), 667-682.

Van Kempen, L. (2004). Are the poor willing to pay a premium for designer labels? A field experiment in Bolivia. Oxford Development Studies, 32(2), 205-224.

Vigneron, F. and Johnson, L. (1999),” A Review and Conceptual Framework of Prestige-Seeking Consumer Behavior,” Academy of Marketing Science Review

Vigneron F, Johnson LW. (2004), Measuring perceptions of brand luxury. Journal of Brand Management 2004; 11(6):484–508

Wasko, M. M &Faraj, S. (2005). Why should I share? Examining knowledge contribution in electronic networks of practice. MIS Quarterly, 29(1), 1-23.

Weidmann, K-P, N. Hennigs, and A. Siebels, (2009), “Value-Based Segmentation of Luxury Consumption Behavior,” Psychology & Marketing, 26 (7), 625-651.

Weissman, P. (1967), “The art of fashion”, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, vol. 26, no. 3, pp. 151-152.

White, S. K. (2015). Consumption motives for luxury fashion products: effect of social comparison and vanity of purchase behaviour.

Xu, Y. (2008), “The influence of public self-consciousness and materialism on young consumers’ compulsive buying”, Young Consumers: Insight and Ideas for Responsible Marketers, Vol. 9 No. 1, pp. 37-48.

Yap, B., W., Ramayah, T., and Shahidan, W., N., (2012). Satisfaction and Trust on Loyalty: a PLS approach. Business Strategy Series, Vol. 13, No. 4, pp. 154-167, ISSN: 1751 -5637.

Zhang, B., & Kim, J.K. (2012). Luxury fashion consumption in China: Factors affecting attitude and purchase intent. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services.

Zhan, L. He. Y., 2011, Understanding luxury consumption in China: consumer perceptions of best-known brands, J. Bus. Res. 65 (10). 1452-1460