|

Shyam S. Lodha Professor of Marketing Southern Connecticut State University New Haven, Connecticut 06515-1355 |

Gene F. Brady Assistant Professor of Management Southern Connecticut State University New Haven, Connecticut 06515-1355 |

Grounded in system economic and marketing theory, the co-evolutionary processes of buyers and sellers in business-to-business markets are examined in terms of their organic complexity; and their needs to innovate, self-organize, become ambidextrous, sustain competencies, and to manage dual learning curves. These processes are examined against backgrounds of potential integrative, as well as disintegrative forces; as well as the dynamics of downstream economics. Caveats for co-managing buyer-seller relationships for the purpose of optimizing synergies are offered.

Key words: Business Markets, Co-Evolution, Edge of Chaos, Learning Curve, Integration, Organic Complexity.

Although co-evolution occurs among several forces within the context of business to business (b2b) markets, i.e., governmental; communities; non-profit organizations; and other stakeholders, the relationship between buyer and seller organizations receives the preponderance of attention in the market and economic literature.Buyers and sellers by nature are highly interdependent. Neither can exist without the other. Further, the development and prosperity of either buyer or seller lies in the capacity of each to draw upon and successfully integrate what the other has to offer in terms of advantages and resources.

The characteristics of buyers vary to include commercial firms; government organizations; and institutions, such as colleges and medical centers. The development of our investigation into buyer-seller co-evolution draws upon three areas of research. One is systems theory, using the broad and interdisciplinary conceptualizations contained in complex systems (CS), and more specifically, complex adaptive systems (CAS). The second is evolutionary economics where special emphasis is devoted to demand-side economics. And, the third area is marketing research, specifically in the area of b2b marketing.

Buyer and Seller as Complex Adaptive Systems

The study of CAS is useful in the study of buyer-seller relationships because the dual entitiesin the relationships represent two interactive and living systems, struggling to adapt to one another as well as with other elements in their respective environments. As organizations, buyer and seller are organically live systems, and not merely metaphors thereof (Pascale, Millerman & Giola, 2001). Amatai Etzioni (1964) further defines organizations as organic social systems with goals. The CAS frame, therefore,permits more organic and evolutionary explanations of co-evolutionary processes than might otherwise be possible using only traditional and mainstream organization theory literature.

Evolving Toward the Edge of Chaos

A central theme of CAS is that living systems, in their fight for survival, naturally evolve toward a domain that is balanced between predictability and randomness. This evolution occurs among both buyer and seller as a self-preservation reaction in an effort to seek out remedies for threats to survival, or to capitalize on opportunitiesfor growth and competitive positioning. This evolution has been further characterized by some as operating at the “edge of chaos (Kauffman, 1993).” To venture too far into the randomized domain carries risk, but may offer the prospect of an adaptive solution to environmental dilemmas. Conversely, to remain in the predictable domain also carries risk – the risk associated with complacency. In mathematical modeling the term Lambda has been applied to measure the degree of randomness at the edge of chaos in any given model. The Lambda parameteris a numbered value between 0 and 1, where values close to zero are in the highly-ordered realm and values close to 1 are in the extremely chaotic realm (Langton, 1991).

Self-Organization

As with organic systems in general, buyers and sellers not only adapt to their respective environments, but contextual elements adapt to them as well.Thus, co-evolution in business markets carries broadly-inclusive connotations. Among the contextual elements, the buyer’s environment includes the seller; the seller’s environment includes the buyer. As co-varying, flexibleand adaptive systems, buyer and seller each alter or discard internal structure that supports predetermined, yet sometimes obsolete, courses of action (Dyer & Erickson, 2007). Operating, as they often do, in fast-moving, continuously-changing markets, buyer and seller, pursue competitive advantages – capitalizing for a while on the efficacy of an idea, and then replacing it when it loses relevance. Although the capability of rapid self-organizing is conducive to adaptation, some shared structure, however temporary, may serve the need for mutual stability, e.g., shared operating platforms, reward mechanisms, transcending leadership, joint committees, central values, liaison, and reciprocal task assignment of personnel (Kanter, 2010). There are levels of risk between buyers and sellers and the two entities do not always treat one another fairly. However, interorganizational trust can be elevated, and risk levels lowered, through such self-organizing mechanisms.Andriopoulas and Lewis (2009) refer to this capacity to productively co-integrate while simultaneously adapting to other forces in the changing environments, as ambidexterity.

To expand the notion of ambidexterity, it is useful that we examine the effect of the respective contextual environments of both buyer and seller. This is important because empirical studies examining buyer-seller processes tend to be more internally focused at the neglect of external characteristics (e.g., Gavetti & Leventhal, 2004). This is understandable when one considers that inward orientations are more immediately translatable to prescriptive management behavior, while contextual orientations tend to take on the need for more intricate interpretations. Internal orientations are often used for close examination of communication and decision-making processes, frequently for the purpose of interorganizational comparison. This, however, is limiting in the absence of some contextual framework (Levinthal, 1997; Zollo & Winter, 2002; Etheraj & Levinthal, 2004).

The inward focus of both the buyer and seller’s strategic choices, along with related contextual characteristics, implies that either system has the awareness needed to make the rational, well-informed and mutually-beneficial decisions consistent with evolutionary models in systems and economic theory (Ericson & Pakes, 1995; Pakes & McGuire, 1994).

Serial Incompetence

Sellers continually seekmethods to attract buyers to their products and services. These methods may come in the form of special discounts and awards. Buyers try to influence the supply chain to become cheaper, speedier, and otherwise more efficient. Eventually, the negotiating tactics that buyer and seller employ across one another are neutralized through obsolescence or duplication by competitors, causing both parties to explore for yet more innovative tactics. Godin (2000) refers to this process of decay and renewal as serial incompetence, which is, more specifically, the tendency of a system to pursue a course of actionas long as it is working. But then, when the course of action is no longer effective, the system will seek more innovative courses of action, or more likely, will seek to bring in new people with fresh ideas. In this way the buyer and seller systems are allowed to venture more precipitously along the edge of chaos.The cliché that “individuals in organizations tend to rise to their levels of incompetence” apply to the organization, as the unit of analyses, as well.

Buyer-side Demand

It is the demand of the individual consumer that ultimately drives theneeds of the buying firm. This consumer demand may occur in two ways. The first is through the increase in the number of consumers, which is indicative of the early stages of the product life cycle. Upon market saturation, however, future growth will depend on the capability of the buyer firm, and possibly the indirect investments of the supplier firm, to entice existing customers to purchase more. Ultimately, it is the expansion of individual consumption that increases demand after market size has reached its peak (Manral, 2015). Fragmentation of downstream markets may also increase demand beyond what might otherwise be construed as peak demand (Manral, 2010). General Electric, for example, refers to this as simply globalization, which is tweaking products to create new sub-markets. Such sub-markets might be characterized by geography, demographics, ethnicity, and the like. These sub-markets may vary in terms of price elasticity around certain product categories. For example, products serving customers at the high end of the market can be re-engineered so as to appeal to customers at the low end. Sub-markets may then serve as downstream expansion through economies of scale and scope.

Both buyer and seller firms increasingly acquire knowledge and skills pertaining to, not only their own environments, but to one another’s environments as they proceed along the learning curve. The learning curve has several components. First, learning is acquired about the differentiation needs of the ultimate consumer during the product development phase (Von Hippel, 1988). Secondly, there is learning associated with production tasks (Spence, 1981). Thirdly, consumers learn what works for them and what doesn’t, compared to competitor’s offerings. Although these learning components benefit the buyer directly, they also indirectly benefit the seller firm by presenting opportunities for cost reduction and by sharpening the focus of the supplier’s advertisement in the buyer’s market (Casadesus-Masanell & Ghemawatt, 2006). In this way, the dynamics of the learning curve might be viewed as 3-dimensional learning, as the customers benefit also from lower prices and more revealing advertisements (Manral, 2010).

Learning and Competencies

The knowledgeable customer base is the foundation of the buyer’s competencies. This customer base may be viewed as an asset, such as in associations or organizations that offer subscription services. This perspective of the customer base as a strategic asset is addressed in the strategic-resource (Zander & Zander, 2005), marketing (Gupta & Lehmann, 2003, 2005, 2006; Gupta, 2009), evolutionary economics (Manral, 2010), and economic literature (Gaurio & Redanko, 2014).

The buyer-firm’s level of competency is reflective of the saliency of its involvement with its customers as well as its accurate appraisement of, and interaction with, industrial forces. The routinization and comfort with the application of these competencies can best be appreciated within the internal context of resource positioning; communication and decision-making processes; and, corporate values and culture.

Both seller and buyer have two broad sets of competency assets: relationships and knowledge – which are intertwined. The saliency of the buyer’s relationship with its existing or prospective customers is significant. This saliency may further intensify as both buyer and seller continue to proceed along their respective learning curves. For the buyer, learning manifests itself in the capability of reducing uncertainties as to customer demands and idiosyncrasies. Progress along the learning curve further enables the motivated buyer-firm to capitalize on opportunities that will satisfy customers and so enhance predictability of their loyalties. The learning curve may be facilitated by certain methodologies, i.e., focus groups, surveys and service logs. Further, pools of information may become richer through sellers’ strategic alliances, mergers and acquisition, and joint ventures. Sellers may also benefit from the resulting information flow, and see opportunities for economies scale and scope (Winter, 1987; Manral, 2010). The buyer’s learning curve overlaps with that of the seller, since the seller is also interested in, and affected by, demand – side consumer behavior. Moreover, the shared portions of the learning curve provide opportunities for the seller to increase knowledge through expanded networks within both the seller’s and buyer’s domains, e.g., acquaintances with influential buyers, centers of buyer’s power, etc.

Costs of Industrial Entry

Aside from the traditional capital and resource requirements that drive competitor buyer-firms to enter the industry, potential entrants face the impossible tasks of overcoming the incumbent buyer’s momentum along the learning curve. The buyer-firm is essentially a moving target. New entrants, however, may not choose to “catch up” to the incumbent. New entrants may not wish to emulate all aspects of the incumbent’s set of competencies and product offerings. Additionally, new entrants may choose different marketing strategies to pursue similar marketing goals, because of different corporate values, structure, personalities and processes. For such reasons, seller firms will not relate symmetrically to buyer firms, whether they be incumbents or new entrants.

Managing the Influx of New Customers

Buyers in business markets ideally pursue two goals simultaneously: One, they attempt to magnify the influx of new customers through referrals and advertisements using different outlets. New customers may also be acquired through expanding markets via M&A, joint ventures and other forms of strategic alliances. Costs and benefits are associated with whichever channels of customer acquisition that is used. This includes costs/benefits accrued through prompting customers to switch, as well as prompting non-customers to start using the product. The process is one of “culling the wheat from the chaff”, and this, too, can be a costly and perplexing endeavor (Blattberg, et. al., 2001). The kind of customer that eventually materializes is influenced by the channel that is used (Bolton, et. al., 2004; Verhoef & Dankers, 2005). Strategically, buyer-firms desire to “buy” customers whose life-span values exceed the total outlays required to keep existing good customers.A second goal is that buyers wish to retain existing customers. The long-term value of the buyer firm’s customers is further enhanced by the capability and willingness of that firm to retain high quality customers. Such retention can be justifiably viewed as an antecedent to the firm’s profitability and strategic value (Reichheld, 1996; Gupta & Lehmann, 2006; Gupta & Zeithaml, 2006). This association is, however, not symmetrical across buyer firms, but is influenced by idiosyncratic methods at the disposal of the firm, e.g., post-sales follow-up, managing complaints, warranties, etc. Additionally, the customers themselves vary by industry, location, demographics, and the channels that are used. These contextual factors can influence customer retention as much as the internal methods employed to gain retention (Mittal & Kamakura, 2001; Ansari, et. al., 2008). The capability of the buyer firm for understanding the customer, and then for being able to customize the product and channel to the customer’s needs serves to lower the propensity of existing customers to switch to competitors. For example, Capital One’s tailored products contributed to 87% customer retention over a span of three years (Capgemini Consulting, 2014).

Expanding Value of Existing Customers

Existing customers can become increasingly valuable in multiple ways. First, they may be induced into buying more of a product – for themselves and perhaps for others (gifts, etc.). Secondly, they can buy upscale versions of the product, such as newer generations of the same model, or a luxury version. Thirdly, they may be persuaded to buy related items, such as when the customer goes on line and sees, “customers purchasing that item also purchase this item.”Fourthly, customers may be influenced to purchase a product with bundled-in items, a tactic that also aids in customer retention as it ups the customers’ switching costs. Fifthly, buyer firms may offer their existing customers alternate channels that are more economical (e.g., on-line, telephone ordering, etc.). The customers may then upgrade their purchases with the money they have saved. Generally, through all of these alternative processes, the buyer is acquiring customer data regarding preferences, buying habits and the like which they can then share with the seller firm, enabling the seller and buyer firms to better co-evolve.

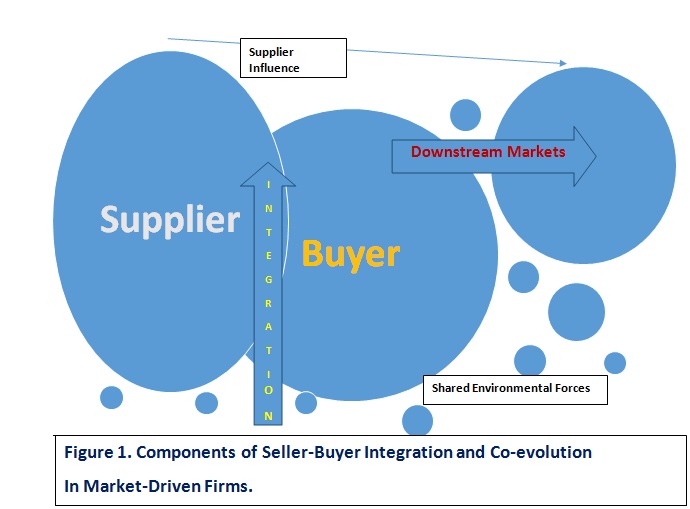

Integrative Forces

In market-driven firms, there are at least two significant competencies that may be shared by both the supplier and the buyer firm. These competencies are market-sensing and customer-linking capabilities. Market-sensing capability addresses the extent that buyer firms can sense and anticipate changes in the downstream markets. Customer-linking capability addresses the set of skills and abilities the market-driven buyer firm has honed to sustain and orchestrate customer relationships. Both buyer and seller are motivated to cooperate in this regard. Specifically, both are motivated to integrate so as to create shared platforms. For example, Proctor and Gamble (P&G) works with Walmart to develop joint multifunctional teams to share delivery and logistical information, promotional schemes, and product research (Hutt & Speh, 2013).Figure 1 illustrates how buyer and seller firms may integrate resources to cater to downstream markets while perhaps facing identical, to some degree, environmental forces. Both buyer and seller firms are influenced by the common denominator, downstream markets, and are thus further motivated to cooperate. Suppliers can often provide unique value to the buyers’ businesses. By working closely together, priceless information may be shared to the benefit of buyers and sellers alike.

Disintegrative Forces

When buyer and seller firms have overlapping or shared agenda, integration of processesor capabilities may provide attractive synergies. Nonetheless, buyer and seller are still separate firms, and their respective agendas may not be compatible. Each firm desires to make a profit, but each firm may take different views as to how to bring this about. Sometimes, the efforts of one to make a profit comes at the expense of the other. For example, in the retail industry Wal-Mart is attempting to declutter its stores in order to make in-store shopping more pleasant for the customer. This effort is not perceived to be in the interest of certain suppliers, like P&G, who would like to see more of their items on the shelf. P&G and Wal-Mart have a long-standing relationship with one another which has led to unprecedented informality between the two giants. In 2015 alone, P&G sold about $10 billion worth of goods through Wal-Mart. Now, this association has become strained as Wal-Mart seeks to sell more goods on-line and to place additional competitively-priced items on in-store shelves. This has especially irked P&G who has failed to keep abreast of lowering prices and innovative new products (Nassauer& Terlep, 2016). This example highlights the customer value proposition that a customer needs to offer (Anderson, Narus & Wouter Van Rossum, 2006). Further in this example, the benefits that P&G once offered as a part of their value proposition has begun to erode as Wal-Mart offers more on-line goods at better prices.

Managing Relationships

In the cited example, Wal-Mart had a long-enduring relationship with P&G that had become so accepting that many of the formalities that Wal-Mart reserved for other customers were not applied. When, however, the relationship began to sour, inertia held the two giants together. It had become like a marriage that was no longer enjoyed, but akin to one held together for the sake of the kids (Nassauer & Terlep, 2016). This example points to the importance of continuous communication and information-sharing throughout all layers of both organizations as both buyers and sellers co-evolve. When the relationship is continually nurtured, high levels of mutual trust and cooperation are more likely to be sustained (Cannon & Perrault, 1999).

Managing Dual Expectations

If the buyer’s relationship with the supplier somehow goes sour, the buyer can choose among contingency supply chains where the points of differences are more attractive. Accordingly, it may be beneficial for both buyer and seller to stay attuned to one another’s expectations, for switching costs can be high. Further, as in the prior example of P&G and Wal-Mart, it might benefit either firm to view the other as a “key account,” whereby the firms jointly develop a transformative form of strategic relationship with one another. In a transformative relationship both sides, through enhanced communication, management and negotiation, attempt to sustain dual synergies into the strategic future.

Our co-evolutionary theoretic framework provides both a demand-side and a supply-side explanation for the co-variation in either firm’s strategic behavior along their industry’s evolutionary path. Buyers and sellers in business markets are living social organisms, albeit social organisms. As such they behave as CAS would predict them to behave, as living systems contending with sometime-hostile environmental forces, including their dependencies on one another, in order to grow and survive. As such, in rapidly evolving markets, both buyers and sellers seek innovative strategies and tactics by surrounding themselves with randomized choices found near the edge of chaos. In such fast-paced markets, traditional organizational structures are impossible to sustain, as both buyer and seller seek not to be constrained in their efforts to seek novel remedies for often unprecedented challenges. Buyer and seller need to co-evolve with one another, as well as each needs to co-evolve with their respective external environments. Some contextual elements affect both buyer and seller as, together, they share overlapping interests. This ability to manage their own evolvement, while simultaneously adapting to the external forces has been referred to as ambidexterity.Both buyer and seller-firms tend to rise to a level of complexity in volatile markets and are challenged to become agile and responsive to the external forces with which each is co-dependent.

As buyer and seller-firms proceed along their respective learning curves their increased awareness ultimately benefits the downstream consumer. As the ultimate asset, the consumer base requires careful treatment, in respect to existing customers as well as the potential influx of new customers. The co-evolution of both seller and buyer-firms has significant potential in terms of synergistic outputs. Thus, effective managing of the cross-relationships comprised in these firms will tend to have elevated status among strategic priorities.

Anderson, J. C., Narus, J. A. & van Rossum, W. 2006. Customer value propositions in business

markets. Harvard Business Review, 84: 91-99.

Andriopoulas, C. & Lewis, M. W. 2009. Explanation-exploration tensions and organizational

ambidexterity: Managing paradoxes of innovation. Organization Science, 20: 696-717.

Ansari, A., Mela, C. F. & Neslin, S. A. 2008. Customer channel migration. Journal of

MarketingResearch, XLV: 60-76.

Blattberg, R. C., Getz, G. & Thomas, J. S. 2001. Customer equity: Building and managing

relationships as valued assets. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Bolton, R. N., Lemon, K. N. & Verhoef, P. C. 2004. The theoretical underpinnings of customer

asset management: A framework and propositions for future research. Journal of the

Academy of Marketing Science, 32: 1-20.

Cannon, J. P. & Perreault, Jr., W. D. 1999. Buyer-seller relationships in business markets.

Journal of Marketing Research, 36: 438-460.

Capgemini Consulting. 2014. Doing business the digital way.

Casadesus-Masanell, R. & Ghemawat, P. 2006. Dynamic mixed duopoly: A model motivated by

Linux vs. Windows. Management Science, 52: 1072-1084.

Dyer, J., Kale P. & Singh, H. 2001. How to make strategic alliances work. MIT Sloan

Management Review, 42: 37-43.

Ethiraj, S. & Levinthal, D. 2004. Modularity and innovation in systems. Management

Science, 50:159-174.

Ericson, R. & Pakes, A. 1995. Markov-perfect industry dynamics: A framework for empirical

work. The Review of Economic Studies, 62: 53-82.

Etzioni, A. 1964. Modern organizations. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Gavetti, G. & Levinthal, D. A. 2004. The strategic field from the perspective of management

science. Management Science, 50: 1309-1318.

Godin, S. 2000. In the face of change the competent are helpless. Fast Company, 230-234.

Gourio, F & Ruedanko, L. 2014. Customer capital. Review of Economic Studies, 81: 1102-

1136.

Gupta, S. 2009. Customer-based valuation. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 23: 169-178.

Hutt, M. D. & Speh, T. We 1984. The marketing strategy center: Diagnosing the industrial

marketer’s interdisciplinary role. Journal of Marketing, 48: 53-61.

Kanter, M. K. 1994. Collaborative advantage. Harvard Business Review, 72: 96-108.

Kauffman, S. A. 1993. Origins of order: Self-organization and selection in evolution. Oxford

England: Oxford University Press.

Langton, C. G. 1991. Life at the edge of chaos in artificial life. Boston: Addison-Wesley.

Levinthal, D. A. 1997. Adaption on rugged landscapes. Management Science, 43: 934-950.

Manral, L. 2010. Toward a theory of endogenous market structure in strategy: Exploring the

endogeneity of demand-side determinants of market structure and firm investment

strategy.Journal of Strategy and Management, 3: 352-373.

Nassauer, S. & Terlep. 2016. The $10 billion tug of war between Wal-Mart and P&G. The Wall

Street Journal, CCLXVII: A1&A10.

Mittal, V. & Kamakura, W. 2001. Satisfaction repurchase intent and repurchase behavior:

Investigating the moderating effects of customer characteristics. Journal of Marketing

Research, 38: 131-142.

Pakes, A. Ostrovsky, M. & Berry, S. 2007. Simple estimators for the parameters of discrete

dynamic games with entry/exit examples. RAND Journal of Economics, 38: 373-399.

Pascale, R. Millerman, M. & Giola, L. 2001. Surfing the edge of chaos, New York: Crown

Business.

Reichfeld, F. F. 1996. The Loyalty Effect, Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Spence, A. M. 1981. The learning curve and competition. Bell Journal of Economics, 12: 49-

70.

Verhoef, P. C. & Donkers, B. 2005. The effect of acquisition channels on customer loyalty and

cross-buying. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 19: 31-43.

Von Hippel, E. 1988. The sources of innovation, New York: Oxford University Press.

Winter, S. G. 1987. Knowledge and competence as strategic assets. In D. J. Teece, Ed., The

competitive challenge: strategies for industrial innovation and renewal, Cambridge,

MA: 159-184.

Zander, I. & Zander, U. 2005. The inner track: On the important (but negative) role of customers

in the resource-based view of strategy and firm growth. Journal of Marketing Studies,

42:1519-1548.

Zollo, M. & Winter, S. G. 2002. Deliberate learning and the evolution of dynamic capabilities.

Organization Science, 13: 339-351.