|

Anand Rai Associate Professor Finance, School of Management JRE Group of Institutions Greater Noida (U.P.) |

Climate change, social degradation, economic crisis and complexities in business have raised serious concern over organisations' sustainability. Sustainability reporting is a broad term considered synonymous with others used to describe reporting on economic, environmental, and social impacts (e.g., triple bottom line, corporate responsibility reporting, etc.). The purpose of a sustainability reporting is the practice of measuring, disclosing, and being accountable to internal and external stakeholders for organizational performance towards the goal of sustainable development.

Currently in India, only few companies have adopted such reporting practices as compared to other developed countries like Japan, USA etc. With the growing concern on social and environmental issues worldwide, this decade is going to see paradigm shift in reporting standards on sustainability.

Global Reporting Initiative is a non-profit organization that works towards a sustainable global economy by providing sustainability reporting guidance. GRI pioneered and developed a comprehensive sustainability reporting framework that is widely used around the world.

This article explores the guidelines of GRI’s sustainability reporting standards. It also unveils recent reporting trends of the Indian organisations on sustainability performances and future prospects.

Keywords: Sustainability, Triple Bottom Line, GRI, Disclosure Frameworks, Corporate Social Responsibility

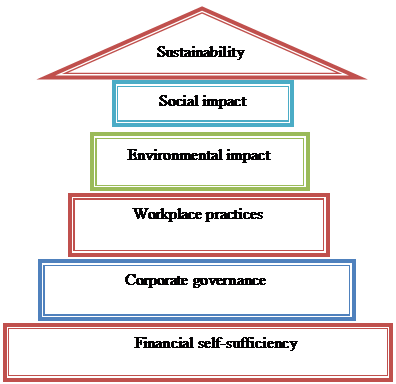

An organisation needs to be financially self sufficient to be able to become sustainable in the long term. Once this primary need for financial capital has been met, the organisation then needs to be socially responsible. This is achieved by ensuring that its governance and workplace practices and its environmental and social impact are self monitoring and conform to society’s expectations and ethical values. Only then a company can achieve sustainability in the long term.

Figure 1: Relationship between sustainability and financial self-sufficiency

In 1919, a landmark judgment was given by the Supreme Court of the State of Michigan, USA in the case of Dodge v. Ford Motor Company. The court said that the primary objective of a business is to make profits and that any business is responsible to its shareholders and not to the community as a whole or to its employees. To date this judgment is treated as a fundamental reference point in relation to the responsibilities of a business and the inherent principle in it has not been overruled by courts.

Nobel

Laureate Milton Friedman (1970) wrote that the responsibility of a business is

to

increase profits and that engaging in activities which discharge the corporate

social responsibilities (CSRs)

of a business is an instance of 'agency

conflict' or a conflict between managers and shareholders. Friedman explains

further that CSR activities are undertaken by

managers to their personal needs and at the expense

of the shareholders. Also, he even went on to say that in a free enterprise

society, CSR reflects an inappropriate use of corporate funds.

Since the early 1980s, social scientists have moved away from the theory of agency as propagated by Friedman and gravitated towards a new model developed by Peston and Caroll, which was embodied in a structure they called the “corporate social performance” (CSP) framework, which combines the principles and philosophy of societal needs with the economic responsibilities of a business.

Freeman (1984) defined stakeholders as “any group or individual who can affect or is affected by the achievements of an organisation's objectives”. The stakeholder’s theory asserts that firms have relationships with many constituent groups and that these stakeholders both affect and are affected by the actions of the firm. In 1984, Freeman argued that the systematic attention of the stakeholders interest is critical to the success of a firm and that management must pursue action that are optimal for a broad class of stakeholders rather than those that serve only to maximise shareholder interests.

These principles set the path for more research and understanding of these theories and led to the integration of the environmental, social and governance responsibilities of a business with the otherwise predominant economic aspects. The stakeholder concept has facilitated the inclusion of the sustainability concept in the core business practices of a company.

The changing global environment is challenging companies to look beyond financial performance to drive business. Business leaders are increasingly realizing the need to integrate environmental and social issues within the business strategy. In a world of changing expectations, companies must account for the way they impact the communities and environments where they operate. Climate change, community health, education and development, and business sustainability are some of the most important issues of this decade. Businesses are increasingly involved in these areas as are their clients and their people. This raises the importance of accurately and transparently accounting for and reporting these activities.

Sustainability means different things to different people. The most often quoted definition is from the Brundtland Commission (1987) which states that sustainable development is "Development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generation to meet their own needs." Sustainability is, therefore, more of a journey that a destination wherein ideals, values and measurement metrics are in a constant state of evolution.

The Triple Bottom Line (TBL), a term coined by Elkington (l997) implies that corporation should focus “not just on the economic value they add but also on the environmental and social value they add – and destroy".

As Deegan (1999) indicated, “for an organisation or community to be sustainable, it must be financially secured (as evidenced through such measures as profitability), it must minimise (or ideally eliminate) its negative environment impact, and it must act in conformity with society’s expectation”.

While Sustainability Reporting is a decade old idea, it is relatively in its early years with the methodology evolving constantly. Still, many nations and organizations have started to understand the concept and incorporate it in their business functions. Sustainability Reporting is a process for publicly disclosing an organizations economic, social and environmental performance. As with any disclosure, the Sustainability Report lays bare the organizations performance to public scrutiny. What distinguishes the Sustainability Report from other reports is the fact that it makes an organization look at its business from every possible quarter in a single document. In an ideal world, the organization’s stakeholders would analyze the report and give constructive feedback to the organization to improve its performance.

But Sustainability Reports need to serve a purpose. It should be possible to derive information and knowledge out of them so that they can be compared across organizations. For this purpose, common standards need to be developed. It was in this context that the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) was founded in 1997 as a project under Ceres, a Boston (US) based national network of investors, environmental organizations and other public interest groups working with companies and investors to address sustainability challenges such as global climate change. In 2002, GRI became an independent international NGO and its secretariat has since been located in Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Its main role was to set up a multi-stakeholder process to define guidance to organizations on what issues they should measure and report on. GRI pioneered and developed a comprehensive sustainability reporting framework that is widely used around the world.

Sustainability reports based on the GRI Reporting framework disclose outcomes and results that occurred within the reporting period in the context of the organization’s commitments, strategy, and management approach. Reports can be used for the following purposes, among others:

i) Benchmarking and assessing sustainability performance with respect to laws, norms, codes, performance standards, and voluntary initiatives;

ii) Demonstrating how the organization influences and is influenced by expectations about sustainable development; and

iii) Comparing performance within an organization and between different organizations over time.

The GRI Reporting Framework is intended to serve as a generally accepted framework for reporting on an organization’s economic, environmental, and social performance. It is designed for use by organizations of any size, sector, or location. It takes into account the practical considerations faced by a diverse range of organizations – from small enterprises to those with extensive and geographically dispersed operations.

The GRI Reporting Framework contains general and sector-specific content that has been agreed by a wide range of stakeholders around the world to be generally applicable for reporting an organization’s sustainability performance.

1. Standard Disclosures: The Guidelines identify information that is relevant and material to most organizations and of interest to most stakeholders. There are three different types of disclosures suggested by GRI.

i) Strategy and Profile: Disclosures that set the overall context for understanding organizational performance such as its strategy, profile, and governance.

ii) Management Approach: Disclosures that cover how an organization addresses a given set of topics in order to provide context for understanding performance in a specific area.

iii) Performance Indicators: Indicators that elicit comparable information on the economic, environmental, and social performance of the organization.

2. Performance Indicators: The Sustainability Performance Indicators is organized by economic, environmental, and social categories. Social Indicators are further categorized by Labour, Human Rights, Society, and Product Responsibility. Each category includes a Disclosure on Management Approach and a corresponding set of Core and Additional Performance Indicators. Core Indicators have been developed through GRI’s multi-stakeholder processes, which are intended to identify generally applicable indicators and are assumed to be material for most organizations. An organization should report on Core Indicators unless they are deemed not material on the basis of the GRI Reporting Principles. Additional Indicators represent emerging practice or address topics that may be material for some organizations, but are not material for others. The Disclosure(s) on Management Approach should provide a brief overview of the organization’s management approach to the Aspects defined under each Indicator Category in order to set the context for performance information. The organization can structure its Disclosure(s) on Management Approach to cover the full range of Aspects under a given category or group its responses on the Aspects differently.

2.1 Economic Performance Indicators: The economic dimension of sustainability concerns the organization’s impacts on the economic conditions of its stakeholders and on economic systems at local, national, and global levels. The Economic Indicators illustrate:

i) Flow of capital among different stakeholders; and

ii) Main economic impacts of the organization throughout society.

Financial performance is fundamental to understanding an organization and its own sustainability. However, this information is normally already reported in financial accounts. What is often reported less, and is frequently desired by users of sustainability reports, is the organization’s contribution to the sustainability of a larger economic system. Following are the economic performance indicators.

Aspect: Economic Performance

EC1 (Core) : Direct economic value generated and distributed, including revenues, operating costs, employee compensation, donations and other community investments, retained earnings, and payments to capital providers and governments.

EC2 (Core): Financial implications and other risks and opportunities for the organization’s activities due to climate change.

EC3 (Core): Coverage of the organization’s defined benefit plan obligations.

EC4 (Core): Significant financial assistance received from government.

Aspect: Market Presence

EC5 (Add): Range of ratios of standard entry level wage by gender compared to local minimum wage at significant locations of operation.

EC6 (Core): Policy, practices, and proportion of spending on locally-based suppliers at significant locations of operation.

EC7 (Core): Procedures for local hiring and proportion of senior management hired from the local community at locations of significant operation.

Aspect: Indirect Economic Impacts

EC8 (Core): Development and impact of infrastructure investments and services provided primarily for public benefit through commercial, in kind, or pro bono engagement.

EC9 (Add): Understanding and describing significant indirect economic impacts, including the extent of impacts.

2.2 Environmental Performance Indicators: The environmental dimension of sustainability concerns an organization’s impacts on living and non-living natural systems, including ecosystems, land, air, and water. Environmental Indicators cover performance related to inputs (e.g., material, energy, water) and outputs (e.g., emissions, effluents, waste). In addition, they cover performance related to biodiversity, environmental compliance, and other relevant information such as environmental expenditure and the impacts of products and services.

Aspect: Materials

CoreEN1 (Core): Materials used by weight or volume.

EN2 (Core): Percentage of materials used that are recycled input materials.

Aspect: Energy

EN3 (Core): Direct energy consumption by primary energy source.

EN4 (Core): Indirect energy consumption by primary source.

EN5 (Add): Energy saved due to conservation and efficiency improvements.

EN6 (Add): Initiatives to provide energy-efficient or renewable energy based products and services, and reductions in energy requirements as a result of these initiatives.

EN7 (Add): Initiatives to reduce indirect energy consumption and reductions achieved.

Aspect: Water

EN8 (Core): Total water withdrawal by source.

EN9 (Add): Water sources significantly affected by withdrawal of water.

EN10 (Add): Percentage and total volume of water recycled and reused.

Aspect: Biodiversity

EN11 (Core): Location and size of land owned, leased, managed in, or adjacent to, protected areas and areas of high biodiversity value outside protected areas.

EN12 (Core): Description of significant impacts of activities, products, and services on biodiversity in protected areas and areas of high biodiversity value outside protected areas.

EN13 (Add): Habitats protected or restored.

EN14 (Add): Strategies, current actions, and future plans for managing impacts on biodiversity.

EN15 (Add): Number of IUCN Red List species and national conservation list species with habitats in areas affected by operations, by level of extinction risk.

Aspect: Emissions, Effluents, and Waste

EN16 (Core): Total direct and indirect greenhouse gas emissions by weight.

EN17 (Core): Other relevant indirect greenhouse gas emissions by weight.

EN18 (Add): Initiatives to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and reductions achieved.

EN19 (Core): Emissions of ozone-depleting substances by weight.

EN20 (Core): NO, SO, and other significant air emissions by type and weight.

EN21 (Core): Total water discharge by quality and destination.

EN22 (Core): Total weight of waste by type and disposal method.

EN23 (Core): Total number and volume of significant spills.

EN24 (Add): Weight of transported, imported, exported, or treated waste deemed hazardous under the terms of the Basel Convention Annex I, II, III, and VIII, and percentage of transported waste shipped internationally.

EN25 (Add): Identity, size, protected status, and biodiversity value of water bodies and related habitats significantly affected by the reporting organization’s discharges of water and runoff.

Aspect: Products and Services

EN26 (Core): Initiatives to mitigate environmental impacts of products and services, and extent of impact mitigation.

EN27 (Core): Percentage of products sold and their packaging materials that are reclaimed by category.

Aspect: Compliance

EN28 (Core): Monetary value of significant fines and total number of non-monetary sanctions for noncompliance with environmental laws and regulations.

Aspect: Transport

EN29 (Add): Significant environmental impacts of transporting products and other goods and materials used for the organization’s operations, and transporting members of the workforce.

Aspect: Overall

EN30 (Add): Total environmental protection expenditures and investments by type.

2.3 Social Performance Indicators: The social dimension of sustainability concerns the impacts an organization has on the social systems within which it operates. The GRI Social Performance Indicators identify key Performance Aspects surrounding labour practices, human rights, society, and product responsibility.

2.3.1 Labour Practices and Decent Work Performance Indicators

Aspect: Employment

LA1 (Core): Total workforce by employment type, employment contract, and region, broken down by gender.

LA2 (Core): Total number and rate of new employee hires and employee turnover by age group, gender, and region.

LA3 (Add): Benefits provided to full-time employees that are not provided to temporary or part time employees, by significant locations of operation.

Aspect: Labor/Management Relations

LA4 (Core): Percentage of employees covered by collective bargaining agreements.

LA5 (Core): Minimum notice period(s) regarding operational changes, including whether it is specified in collective agreements.

Aspect: Occupational Health and Safety

LA6 (Add): Percentage of total workforce represented in formal joint management–worker health and safety committees that help monitor and advise on occupational health and safety programs.

LA7 (Core): Rates of injury, occupational diseases, lost days, and absenteeism, and total number of work-related fatalities, by region and by gender.

LA8 (Core): Education, training, counselling, prevention, and risk-control programs in place to assist workforce members, their families, or community members regarding serious diseases.

LA9 (Add): Health and safety topics covered in formal agreements with trade unions.

Aspect: Training and Education

LA10 (Core): Average hours of training per year per employee by gender, and by employee category.

LA11 (Add): Programs for skills management and lifelong learning that support the continued employability of employees and assist them in managing career endings.

LA12 (Add): Percentage of employees receiving regular performance and career development reviews, by gender.

Aspect: Diversity and Equal Opportunity

LA13 (Core): Composition of governance bodies and breakdown of employees per employee category according to gender, age group, minority group membership, and other indicators of diversity.

Aspect: Equal Remuneration for Women and Men

LA14 (Core): Ratio of basic salary and remuneration of women to men by employee category, by significant locations of operation.

LA15 (Core): Return to work and retention rates after parental leave, by gender.

2.3.2 Human Rights: There is growing global consensus that organizations have the responsibility to respect human rights. Human rights Performance Indicators require organizations to report on the extent to which processes have been implemented, on incidents of human rights violations and on changes in the stakeholders’ ability to enjoy and exercise their human rights, occurring during the reporting period. Among the human rights issues included are non discrimination, gender equality, freedom of association, collective bargaining, child labor, forced and compulsory labor, and indigenous rights.

Human Rights Performance Indicators

Aspect: Investment and Procurement Practices

HR1 (Core): Percentage and total number of significant investment agreements and contracts that include clauses incorporating human rights concerns, or that have undergone human rights screening.

HR2 (Core): Percentage of significant suppliers, contractors, and other business partners that have undergone human rights screening, and actions taken.

HR3 (Core): Total hours of employee training on policies and procedures concerning aspects of human rights that are relevant to operations, including the percentage of employees trained.

Aspect: Non-discrimination

Core

HR4 (Core): Total number of incidents of discrimination and corrective actions taken.

Aspect: Freedom of Association and Collective Bargaining

HR5 (Core): Operations and significant suppliers identified in which the right to exercise freedom of association and collective bargaining may be violated or at significant risk, and actions taken to support these rights.

Aspect: Child Labor

HR6 (Core): Operations and significant suppliers identified as having significant risk for incidents of child labor, and measures taken to contribute to the effective abolition of child labor.

Aspect: Forced and Compulsory Labor

HR7 (Core): Operations and significant suppliers identified as having significant risk for incidents of forced or compulsory labor, and measures to contribute to the elimination of all forms of forced or compulsory labor.

Aspect: Security Practices

HR8 (Add): Percentage of security personnel trained in the organization’s policies or procedures concerning aspects of human rights that are relevant to operations.

Aspect: Indigenous Rights

HR9 (Add): Total number of incidents of violations involving rights of indigenous people and actions taken.

Aspect: Assessment

HR10 (Core): Percentage and total number of operations that have been subject to human rights reviews and/or impact assessments.

Aspect: Remediation

HR11 (Core): Number of grievances related to human rights filed, addressed and resolved through formal grievance mechanisms.

2.3.3 Society: Society Performance Indicators focus attention on the impacts organizations have on the local communities in which they operate, and disclosing how the risks that may arise from interactions with other social institutions are managed and mediated. In particular, information is sought on the risks associated with bribery and corruption, undue influence in public policy-making, and monopoly practices.

Society Performance Indicators

Aspect: Local Communities

SO1 (Core): Percentage of operations with implemented local community engagement, impact assessments, and development programs.

SO2 (Core): Operations with significant potential or actual negative impacts on local communities.

SO3 (Core): Prevention and mitigation measures implemented in operations with significant potential or actual negative impacts on local communities.

Aspect: Corruption

SO4 (Core): Percentage and total number of business units analyzed for risks related to corruption.

SO5 (Core): Percentage of employees trained in organization’s anti-corruption policies and procedures.

SO6 (Core): Actions taken in response to incidents of corruption.

Aspect: Public Policy

SO7 (Core): Public policy positions and participation in public policy development and lobbying.

SO8 (Add): Total value of financial and in-kind contributions to political parties, politicians, and related institutions by country.

Aspect: Anti-Competitive Behavior

SO9 (Add): Total number of legal actions for anticompetitive behavior, anti-trust, and monopoly practices and their outcomes.

Aspect: Compliance

SO10 (Core): Monetary value of significant fines and total number of non-monetary sanctions for noncompliance with laws and regulations.

2.3.4 Product Responsibility: Product Responsibility Performance Indicators address the aspects of a reporting organization’s products and services that directly affect customers, namely, health and safety, information and labelling, marketing, and privacy. These aspects are chiefly covered through disclosure on internal procedures and the extent to which these procedures are not complied with.

Product Responsibility Performance Indicators

Aspect: Customer Health and Safety

PR1 (Core): Life cycle stages in which health and safety impacts of products and services are assessed for improvement, and percentage of significant products and services categories subject to such procedures.

PR2 (Add): Total number of incidents of non-compliance with regulations and voluntary codes concerning health and safety impacts of products and services during their life cycle, by type of outcomes.

Aspect: Product and Service Labelling

PR3 (Core): Type of product and service information required by procedures, and percentage of significant products and services subject to such information requirements.

PR4 (Add): Total number of incidents of non-compliance with regulations and voluntary codes concerning product and service information and labelling, by type of outcomes.

PR5 (Add): Practices related to customer satisfaction, including results of surveys measuring customer satisfaction.

Aspect: Marketing Communications

PR6 (Core): Programs for adherence to laws, standards, and voluntary codes related to marketing communications, including advertising, promotion, and sponsorship.

PR7 (Add): Total number of incidents of non-compliance with regulations and voluntary codes concerning marketing communications, including advertising, promotion, and sponsorship by type of outcomes.

Aspect: Customer Privacy

PR8 (Add): Total number of substantiated complaints regarding breaches of customer privacy and losses of customer data.

Aspect: Compliance

PR9 (Core): Monetary value of significant fines for noncompliance with laws and regulations concerning the provision and use of products and services.

With increasing importance of India as a global economy and its role at crucial international forums dealing with economic and climate change issues, the Finance Ministry decided in 2011 to expand the scope of the annual Economic Survey to include a chapter on the topic of financing of climate change. The survey discusses the effect of climate change in India, the government initiatives, financing and overall strategy.

India has many publicly-funded programs for the prevention and control of climate risks and issues relating to sustainable development. One of the major objectives of many rural development and poverty upliftment programmes is the reduction of vulnerability to risks arising out of climate change.

Banks have been assigned a special role in the economic development of the country, and the Reserve Bank of India, the banking regulator, has prescribed that certain percentage of bank lending should be allocated to developmental sector called the “Priority Sector”. In addition, banks have begun to realise their role as multipliers for responsible and sustainable business as they increasingly integrate evaluation on sustainability as one of the key inputs to their decision on financing and valuation of projects. Similarly, the Charter on "Corporate Responsibility for Environmental Protection (CREP)" from Ministry of Environment & Forest (MoEF) looks beyond the compliance of regulatory norms for prevention & control of pollution through various measures including waste minimisation, in-plant process control & adoption of clean technologies. The Charter set targets concerning conservation of water, energy, recovery of chemicals, reduction in pollution, elimination of toxic pollutants, process & management of residues that are required to be disposed of in an environmentally sound manner, listing action points for pollution control for various categories of highly polluting industries.

Financial reporting in India includes mandatory reporting on environment and social matters such as on consumption of energy, use of raw materials and intermediaries, conservation efforts, accounting for environment cost, and disclosures on liability for environment issues. Labour and industrial laws are also well established and companies are required to report on matters such as salaries, wages and benefits paid to employees and the status of payment towards retirement and social benefits.

The Ministry of Corporate Affairs released Voluntary Guidelines on Social, Environmental and Economic Responsibilities of Business (NVGs) in July 2011 after considerable stakeholder consultations. They are compatible with globally acceptable guidelines on sustainability reporting. The GRI focal point India and the GIZ India have supported and promoted the creation of the NVG through the IICA-GIZ CSR Initiative.

Recently, the department of public enterprises has issued guidelines on Sustainable Development and CSR for Central Public Sector Undertakings (CPSEs). These guidelines stipulate how much and how CPSEs should invest and report on Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). The CSR budget mandated range from 0.5 percent to 5 percent of the profit depending on the net profit of the CPSE.

A recent decision taken by the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) mandates that listed entities should submit Business Responsibility report as a part of their annual reports, which would describe measures taken by them along the key principles enunciated in the 'National Voluntary Guidelines on Social, Environmental and Economic Responsibility of Business' (NVGs) framed by the Ministry-of Corporate Affairs (MCA).

To start with, this requirement would be applicable to the top 100 companies in terms of market capitalisation and would be extended to other companies in a phased manner. This decision indicates the importance that the Government of India places on the fulfilment of environmental, social and governance responsibilities of businesses.

The new Company's Bill tabled in the Parliament in December 2011 is a key steps towards strengthening corporate governance and business sustainability measures. The new Bill suggest that Every company with a net worth exceeding Rs. 5 billion or a turnover exceeding Rs. 10 billion or profit exceeding Rs. 50 million should form a committee of three or more directors, including at least one independent director, to recommend activities for discharging corporate social responsibilities in such a manner that the company would spend at least 2 percent of its average profits of the previous three years on CSR. The company is also required to disclose its activities in its report or on its website, and to institute a formal policy on CSR.

Indian companies have been reporting on sustainability since 2001 by using the GRI Framework, following the Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP) or completing the UN Global Compact's Communication of Progress (CoP). The process of evolution for most companies has been to initiate the reporting process under the CDP or the UNGC CoP, and later progress into reporting under the GRI Framework, which is based on both principles and standard disclosures, including performance indicators. However, a small number of companies report under all the three reporting norms. The number of companies reporting on sustainability has been increasing but is still relatively small as compared to the total number of companies that are publicly traded in India.

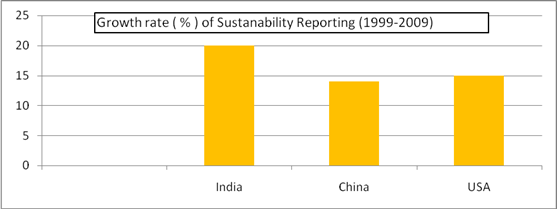

The first version of the GRI Guidelines was issued in 2000. A second generation of the guideline known as G2 was unveiled in 2002 at the World Summit on Sustainable Development in Johannesburg. Some Indian companies started reporting on the G2 framework from the year it was launched in 2002. Since then, the number of reporting companies has increased steadily over the years. It can also be observed that the growth rate of sustainability reporting is higher in India as compared to China and USA in the period from 1999 to 2009.

Figure-2: Growth rate in Sustainability Reporting

Source: GRI Sustainability Report

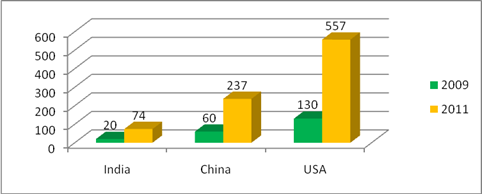

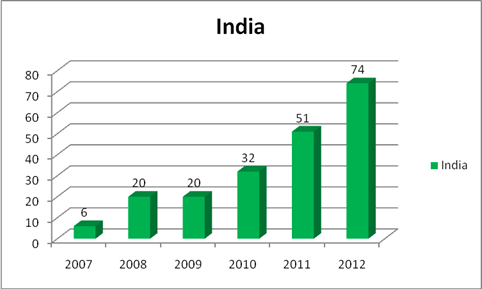

GRI launched the third generation of its Guidelines, G3, in 2006 and Indian companies transitioned to the G3 Guidelines in 2007; all reports since 2009 are based on the G3 guidelines. In a recent analysis by GRI, it has been observed that Indian companies are producing the highest proportion of complete report globally, implying the disclosure of a complete set of information that is relevant to the reporting organisation and external assurance. In March 2011, GRI published the G3.1 guidelines - an update and completion of G3, with expanded guidance on reporting gender, community and human rights- related performance - and Indian companies are adapting to these new changes in the reporting framework. There are around 80 Indian companies from various sectors that have been reporting and there are about 60 companies that publicly declare that they use the GRI guidelines, although only 74 sustainability reports are registered on the GRI database. Most of these reports disclose information on almost all aspects of performance indicators ranging from environment, social and governance, although the rigour and details vary.

Figure-3: Number of Companies Reporting Sustainability

Source: GRI Sustainability Report

Figure-4: Number of Companies Reporting Sustainability in India

Source: GRI Sustainability Report

A recent study by University of Leeds and Euromed Management School, France based on an analysis of over 4000 CSR reports concluded that the reports have been fraught with irrelevant data, unsubstantiated claims, and gaps in data and inaccurate data and suggest that missing rigour and voluntary action results in lower public trust in such reports.

Unlike financial reporting, the disclosure of sustainability metrics to the market is largely unregulated and predominantly voluntary. However, as sustainability becomes a critical factor in the business environment it would become important for companies to build a framework for these processes, information systems and controls that match the quality and focus observed in financial reporting. A third party assurance, in this direction, may ensure quality and consistency of disclosures. It involves verification, which is an independent, documented and systematic process of scrutinizing data, its associated processes and methods for collection and its management, which leads to an assurance statement. This indicates the reliability of disclosures and demonstrates credibility of the organization to its stakeholders.

Trends in external assurance of sustainability reports based on the GRI framework from India reveals a rise in external assurance from 10% in 2006 to more than 70% in 2010. This rise in percentage is significant more so when coupled with the rise in number of GRI reports from Indian industry. It is worthwhile to note that GRI recommends the use of external assurance

India is acknowledged as one of the fastest growing economies in the world; as a result, it faces the challenge of balancing fuel consumption, and its rapid growth with the equitable conservation of its key resources, and managing the impact on society. Although corporate responsibility seems to be in the experimental phase in India as of now, significant progress in both the number of reports and quality of information reported is expected in the coming years. The expectations form Indian reporters going forward is to focus on presenting information related to:

i) Sustainability issues, challenges, dilemmas and opportunities.

ii) Regulatory environment and fact-based information.

iii) Information of interest to investors such as materiality of issues in financial terms, vision and strategy statements, goals and targets, etc.

iv) Explanation on identification and prioritization of material issues.

v) Reader friendly report design.

At the regulatory level, various directives have been issued and with some still in pilot stage. The Institute of Chartered Accountants of India (ICAI) has set up the ICAI – Accounting Research Foundation (ICAI-ARF), which has undertaken a special project to suggest a suitable framework for sustainability reporting for Indian companies. Further, the Ministry of Corporate Affairs, Government of India in association with the Indian Institute of Corporate Affairs has released the voluntary guidelines on social, environmental and economic responsibilities of business. In the financial sector, there is a visible trend to promote environmentally and socially responsible lending and investment, with the Reserve Bank of India recently issuing a circular for highlighting role of banks in promoting sustainable development.

There is no doubt that corporate responsibility is here to stay and businesses have realized the value of embracing sustainability and more so making it a part of their overall business strategy.

Carroll, A., (1979), A three dimensional model of corporate performance, Academy of Management Review, no. 4, pp. 99-120.

Deegan, C. (1997), “A Triple Bottom Line Reporting: A new approach for sustainable Organisation” Charter, April, Vol.70, pp. 38-40.

Elington, J. (1997), “Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business”, Oxford Capstone Publishing.

Finch, Nigel (2005), “The Motivation for Adopting Sustainability Disclosure”, MGSM Working Paper no. 2005-17, Available SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=798724

Friedman, M., (1962), Capitalism and Freedom, University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Freidman, M., (1970), The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits, New York Times, September 13, pp. 122-126.

Freeman, R. Edward (1984), Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach, Boston Pitman, USBN 0273019139.

Gelb, D. and Strawser, J. (2001), "Corporate Social Responsibility and Financial disclosure: An alternative explanation for Increased Disclosure”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol.33, No.1, pp. 1-13.

https://www.globalreporting.org/resourcelibrary/G3.1-Guidelines-Incl-Technical-Protocol.pdf

http://www.earthsummit2012.org/historical-documents/the-brundtland-report-our-common-future.

Mc William, A. and Siegel, D. (2001), “Corporate Social Responsibility: A Theory of the Firm Perspective”, Academy of Management Review, Vol.1, No.26, pp. 117-27.